Sight unveiled

Image and memory in early modern ephemeral culture

Félix Díaz Moreno • Miguel Hermoso Cuesta • Sara Mamone • Ramón Pérez de Castro • Anna Maria Testaverde

Leonardo da Vinci. Studies of proportions of the face and eye, with notes, pen, brown ink on paper, c. 1489-1490, Turin, Musei Reali-Biblioteca Reale, Inv. D.C. 15574 e D.C. 15576, coll. Dis.It.Scat.1.21r e Dis.It.Scat.1.20r. Courtesy of the MiC-Musei Reali, Biblioteca Reale of Turin, photo: Ernani Orcorte.

The meaning of seeing, the experience of looking

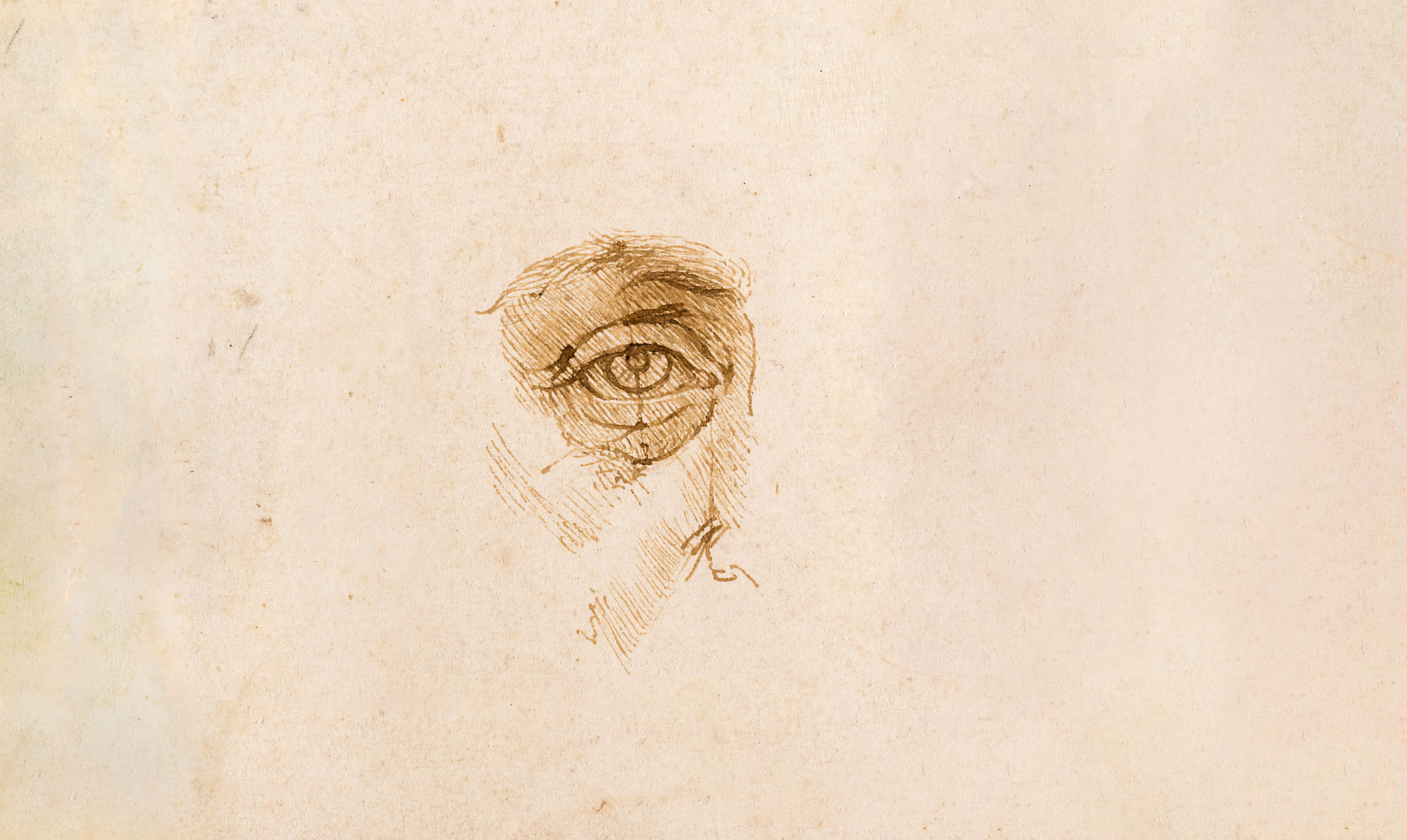

The eye perceives changes in light. Our brain processes the visual stimuli received in this way into images. The eye is therefore the main organ of vision and perhaps the most important of all senses for humans. What we perceive in the physical world through sight is remembered, abstracted, recreated, changed and evaluated at the level of imagination. It is imprinted on our memory together with other synesthetic stimuli and is stored by our mind in a kind of multisensory library. It is not a coincidence that that word imagination is derived from imago (image).

Let’s embark on a visual tour that presents festivals and artifacts from the Early Modern Period and at the same time deals with seeing itself and its processes. Here the sacred mixes with the profane and the religious with the political and didactic.

Take part in a selection of historical festivals! You will see three churches and a famous painting with new eyes and discover and understand their historical and mythological backgrounds.

Four views on the gaze

Sight is not only an instrument for capturing images, but a vehicle for a deeper transmission of messages. It is a mirror of the soul, a source of aesthetic pleasure, an intellectual element, a mechanism of knowledge and a vehicle for ideological orientation. It is not enough to see, it is necessary to know how to look.

Discours de la methode pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la verité dans les sciences. Plus, la dioptriqve. Les meteores. Et la geometrie. Qui sont des essais de cete [sic] methode / [René Descartes]. 1637

Source: Wellcome Collection.

Credits

| Title | Sight unveiled Image and memory in early modern ephemeral culture |

| Coordination | Félix Díaz Moreno |

| Authors | Félix Díaz Moreno, Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, Sara Mamone, Ramón Pérez de Castro, Anna Maria Testaverde |

| English proofreading | Alexander McCargar |

| Voices | Alexander McCargar, Rudi Risatti |

Memory and Tradition

Funerals in Florence for Philip II (1598) and Margaret of Austria (1612)

Sight is arguably the main sense of all human perception, and all the more so at celebratory and public events.

This is why it seemed important to us in the sensory tours section to devote specific attention to it. Not sight tout court (which is also a substantial element in the other sensory exhibitions) but a specific approach that identifies and relates the intentions of each commission filtered through sight itself. In other words, not what is seen but the discourse that is conveyed through sight in the relationship between the client and the recipient(s). From the examples chosen around scenographic culture, we have selected two similar ceremonial events (The funerals in Florence of Philip II and Margaret of Austria) which we will use to show the process of capturing the image, in veiling and unveiling, through the progressive process of appropriation of the images themselves, the intentions of the patrons and artists.

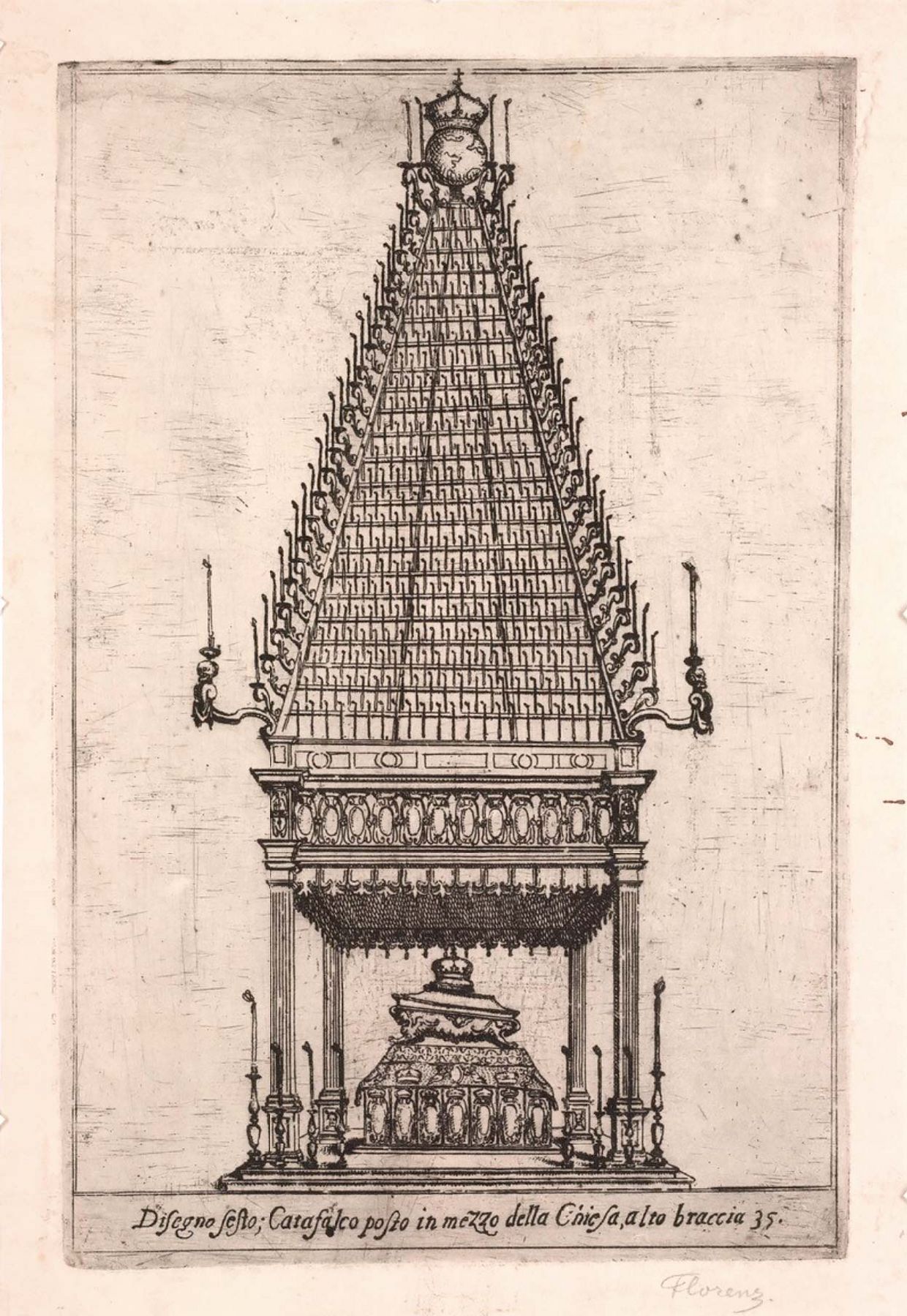

For the funerals of Philip II in 1598 and Margaret of Austria in 1612, a complex funeral apparatus with large painted canvases was built and exhibited in Florence in the Church of San Lorenzo.

It extended along the nave up to the catafalque. The spectator could follow and retrace with his or her gaze the most important episodes in the life of Grand Duke Ferdinand. The episodes were chosen by the Duke himself and the artists of his entourage, without forgetting, of course, those that connected the Medici family to Spanish politics.

Following the historical sources, we will dwell on the church's apparatus and especially on the itinerary that leads the visitor from the entrance of the church to the place of the catafalque. We will examine several of the images that we consider highly significant for illuminating that special process of veiling and unveiling, achieved through the sense of sight. From there, we will then focus on some of the most significant historical episodes displayed by the apparatus. The entire experience represents a didactic procedure that leads the spectator not to a personal or generic vision but to a ‘teleguided’ one.

The same procedure will be implemented for the funeral of Philip II and Margaret of Austria.

The Sumptuous funerals

... celebrated in Florence for Philip II and Margaret of Austria were “effigy funerals”, a type of funeral that was very frequent among the Medici, who had well understood the importance of reaffirming blood relations and alliances with the great courts of Europe.

Philip II was father-in-law of Margaret of Austria, whose sister, among other things, was the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, Maria Maddalena, wife of the reigning Grand Duke Cosimo II. Their deaths were, therefore, a wonderful opportunity that allowed the Grand Duchy of Tuscany to place itself on an equal footing with its important deceased relatives. Of all the types of self-representation, the funeral display most clearly allows for the transformation of the eulogy into self-praise, through the description of the life and virtues of the deceased. This practice is clearly supported and documented by the official descriptions of the time.

The apparatus set up in the Basilica of San Lorenzo, which had long been the place par excellence for the ceremonies of the Medici family, compelled visitors to rest their gaze on images which were functional to the grand ducal ideology. Skillfully, through a kind of teleguided vision, the choreographed visual path becomes cerebral and restores the memories of historical moments which constitute a Medici tradition.

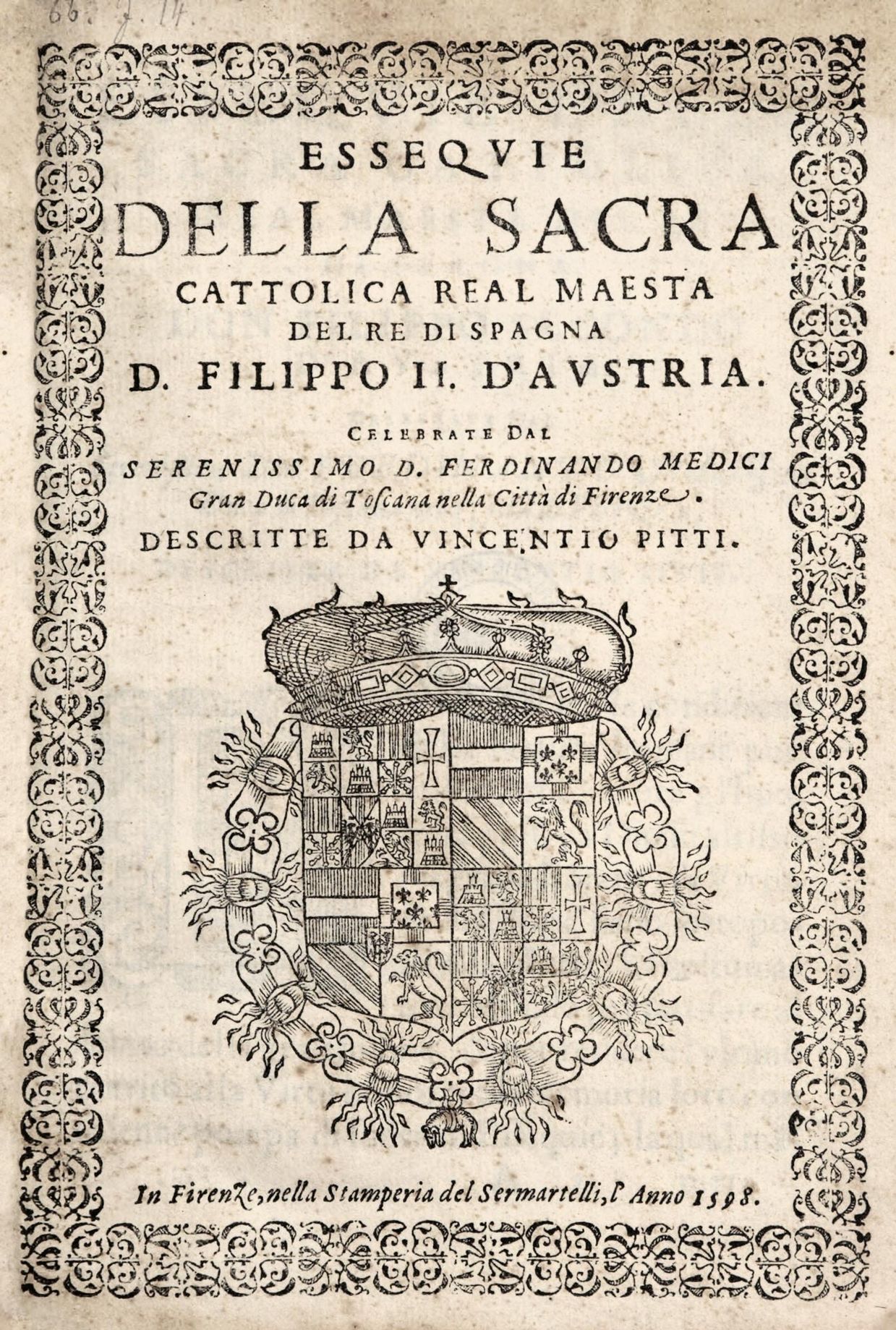

The funeral for Philip II of 1598

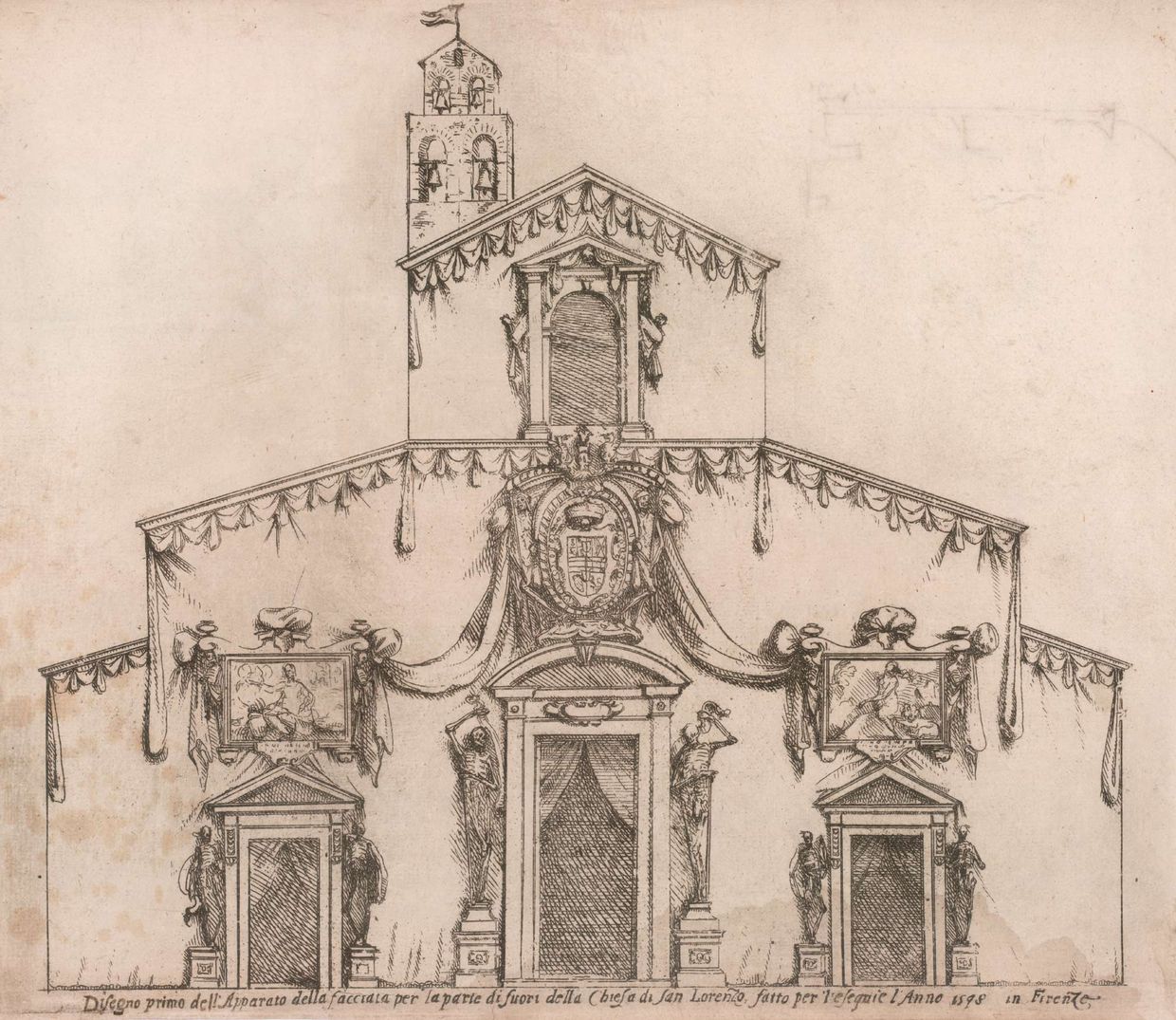

Giovan Battista Mossi, Main facade of San Lorenzo, 1598. Vienna, Albertina, Inv. DG2014/104/1.

«Vedevası adunque al primo incontro tutta di panni neri coperta, da quella parte in poi che con il dorso della Chiesa sopra sta all’ali che da lato gli sono, & questa lontana dalla vista come disutile all’apparato, indietro fu lasciata. Sopra de’ quali altri simili con diverse in volture, nodi, & pieghe in tal maniera s’ingruppavano insieme che con mesta vaghezza li distendevano da ogni lato fino a gl’ultimi estremi di lei, & à quelli intorno con simili avvolgimenti davano bello & proportionato complimento.»

At the first sight, therefore, [the facade] was all covered with black cloths, from that part of the back of the Church above the wings that are on its side, and this, out of sight as useless to the apparatus, was left behind. On top of which others of a similar nature were gathered together in such a way that they stretched them out from each side to the ends of the Church with sad vagueness, and with similar windings they gave those around them a beautiful and proportionate fulfillment.

Vincentio Pitti, Essequie della sacra cattolica real maesta del re di Spagna D. Filippo II. D’Austria. Nella stamperia del Sermatelli, In Florence, 1598, p. 8.

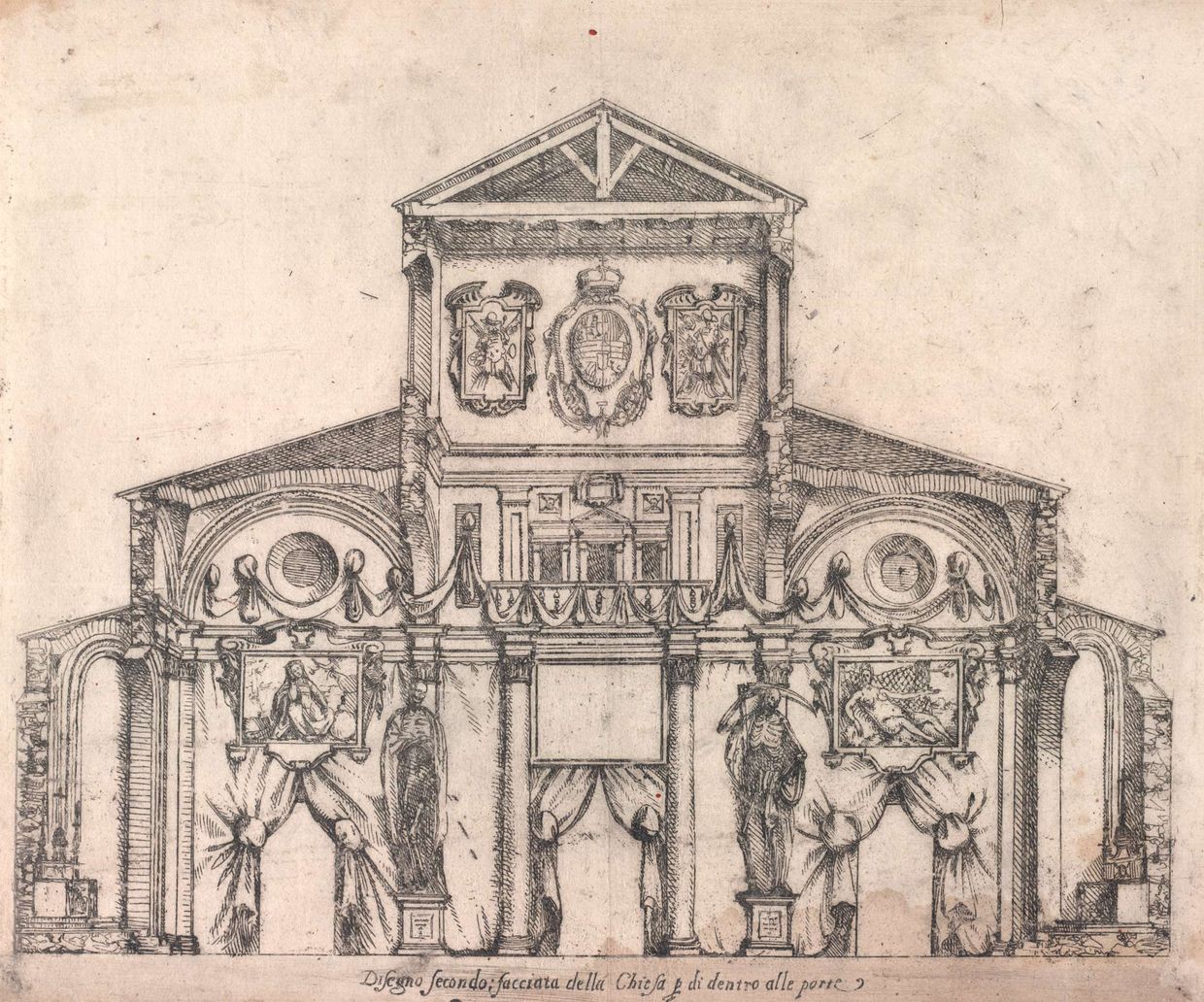

Giovan Battista Mossi, The Interior of the Main Facade of San Lorenzo, 1598. Vienna, Albertina , Inv. DG2014/104/2.

«…ma l’invenzione non havendo l’intero suo complimento, andava à terminare sopra le medesime Porte dentro la Chiesa; sopra le quali erano due altre donne simili meste e dolenti, in questo però da quelle differenti che come quelle in atto humile di pregare e d’invitare, cosi queste di gratamente accogliere gl’invitati facevano sembianża » .

…but the invention did not have its entire fulfillment, so it ended at the same doors inside the Church; above them were two other similar mournful and sorrowful women, but differing in that, as the former were in the humble act of praying and inviting, so the latter were graciously welcoming the guests, making a semblance.

Vincentio Pitti, Essequie della sacra cattolica real maesta del re di Spagna D. Filippo II. D’Austria. Nella stamperia del Sermatelli, In Florence, 1598, p. 11.

These images illustrate the layout of the two facades (external and internal) of the Basilica of San Lorenzo.

It is interesting to note the functioning of the double apparatus. One part presents itself to the spectators who approach the basilica building from Piazza San Lorenzo, the heart of the Medici district in Florence. The other, after a one hundred and eighty degree rotation, presents the fourth wall inside the church chosen for dynastic consecrations and memorials and places the viewer in the best position to evaluate the interior funeral apparatus.

Inside the church, Ferdinand I, Grand Duke and commissioner of the work, is in dialogue with history: that of his family and that of the illustrious deceased. The reading of the chosen episodes takes place entirely according to a precise and peremptory dramaturgy of the gaze, which requires the viewer to focus on the celebratory program and eulogy entrusted to the court artists.

The interior funeral apparatus

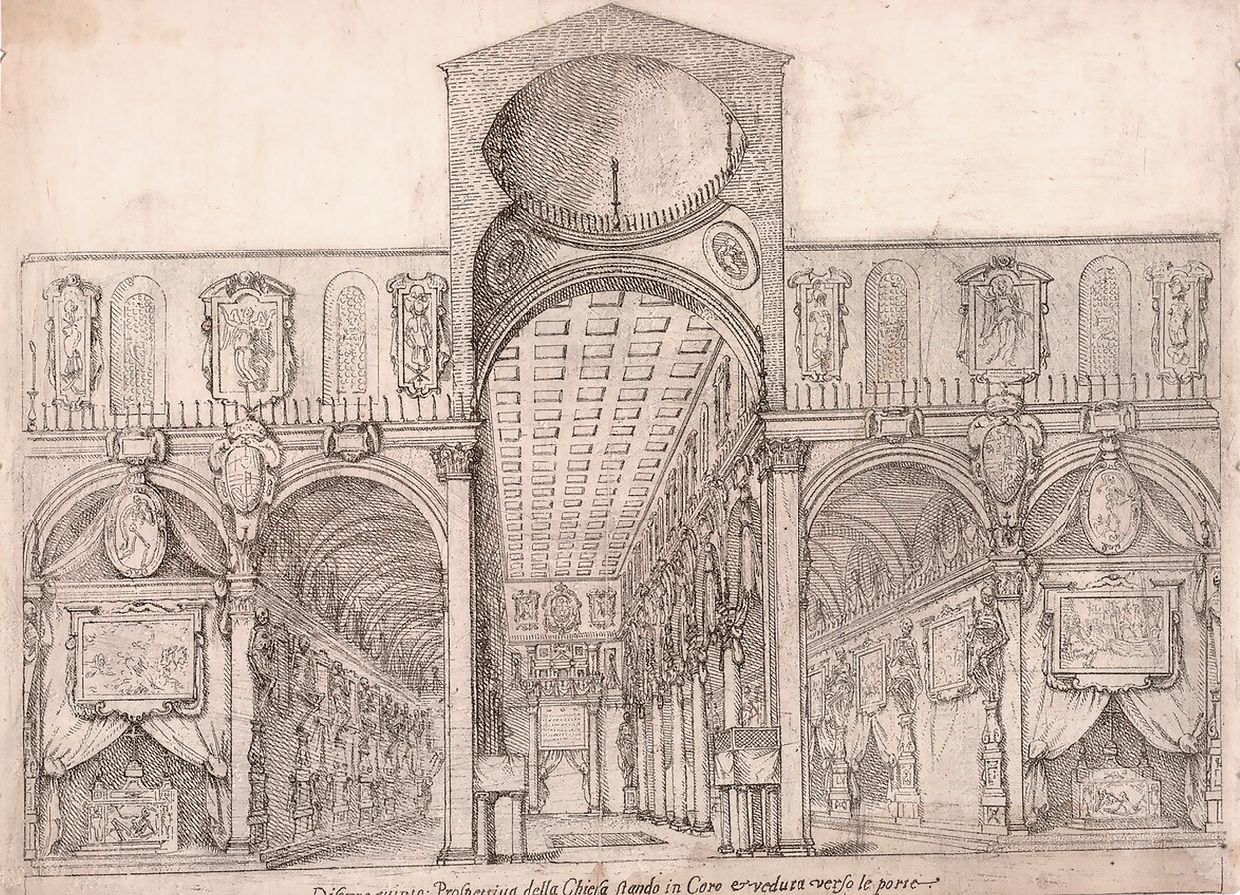

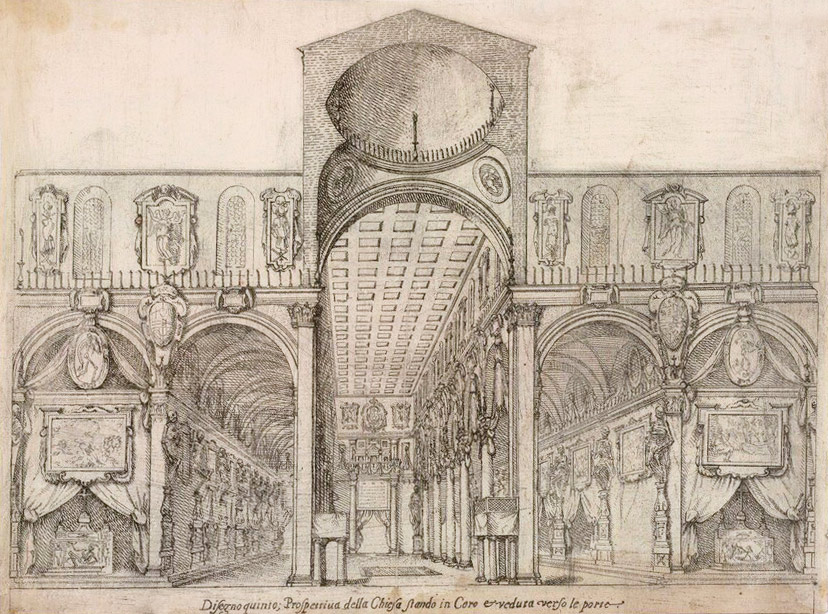

Giovan Battista Mossi, Interno di San Lorenzo, 1598. Vienna, Albertina, Inv. DG2014/104/5.

«La Nave maggiore, che da duoi Pilastri i quali la Porta più grande mettono in mezzo piglia il principio, per quanto si distendono le Navi minori, per tante Colonne della medesima pietra quanti sono i Pilastri delle Cappelle, da loro distinta, da due gran Pilastri in poi, che in luogo di esse nell’ultimo termine son’ posti; e questi in alto stendendosi con nobilissimo Arco reggono la Cupola, in compagnia però di dua corrispondenti i quali oltre al medesimo uficio formano la testa della Croce, dentro la quale la Cappella maggiore è riposta; & ambi insieme con nobilissimi Archi abbracciati il tetto della Chiesa sostentano…»

The main Nave, which from two Pillars, which place the greatest Door in the middle, begins, as far as the minor naves extend, by means of as many Columns of the same stone as there are Pillars of the Chapels, distinguished by them, from two great Pillars onwards, which are located in place of them at the last end; and these, stretching upwards with a most noble Arch, support the Dome, with, however, two corresponding ones, which, in addition to the same task, form the head of the Cross, within which the great Chapel is placed; & both together, with most noble Arches, support the roof of the Church…

Vincentio Pitti, Essequie della sacra cattolica real maesta del re di Spagna D. Filippo II. D’Austria. Nella stamperia del Sermatelli, In Florence, 1598, pp.14–15.

The previous drawing illustrates the ephemeral apparatus built inside the church on occasion of the funeral. Note how along the aisles numerous paintings were temporarily set up one after the other.

Vincenzo Pitti’s description continues by mentioning the catafalque installed in front of the altar, and is entirely focused on the light effects of the apparatus, which become an imperious metaphor of power.

The life of Philip II

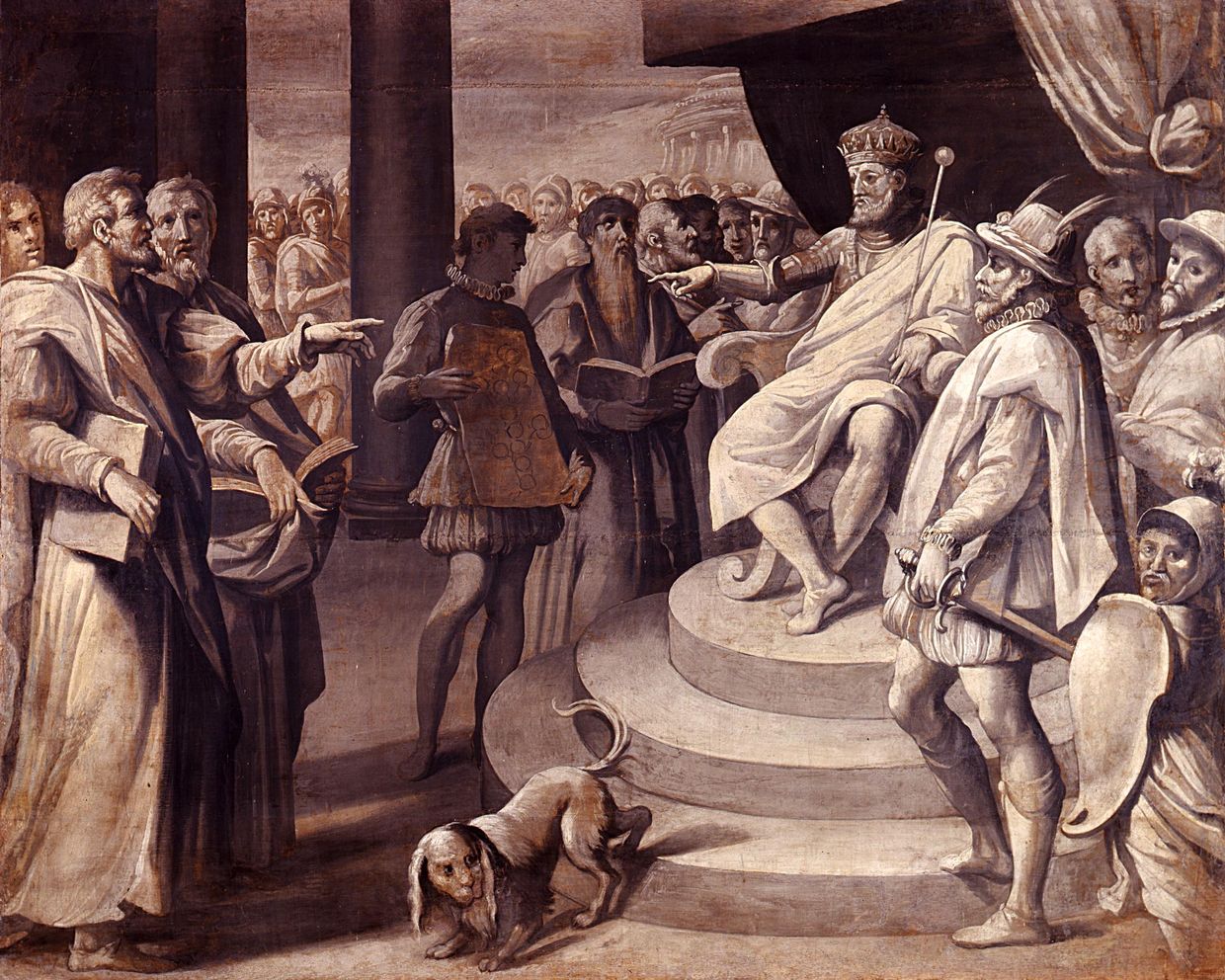

Many events in the life of Philip II testify to the greatness of the king and his empire. From the entire biographical cycle, we have chosen three of the most important episodes, which are shown in the following paintings. These surviving originals canvases were exhibited inside the church and are now kept in the Uffizi Galleries.

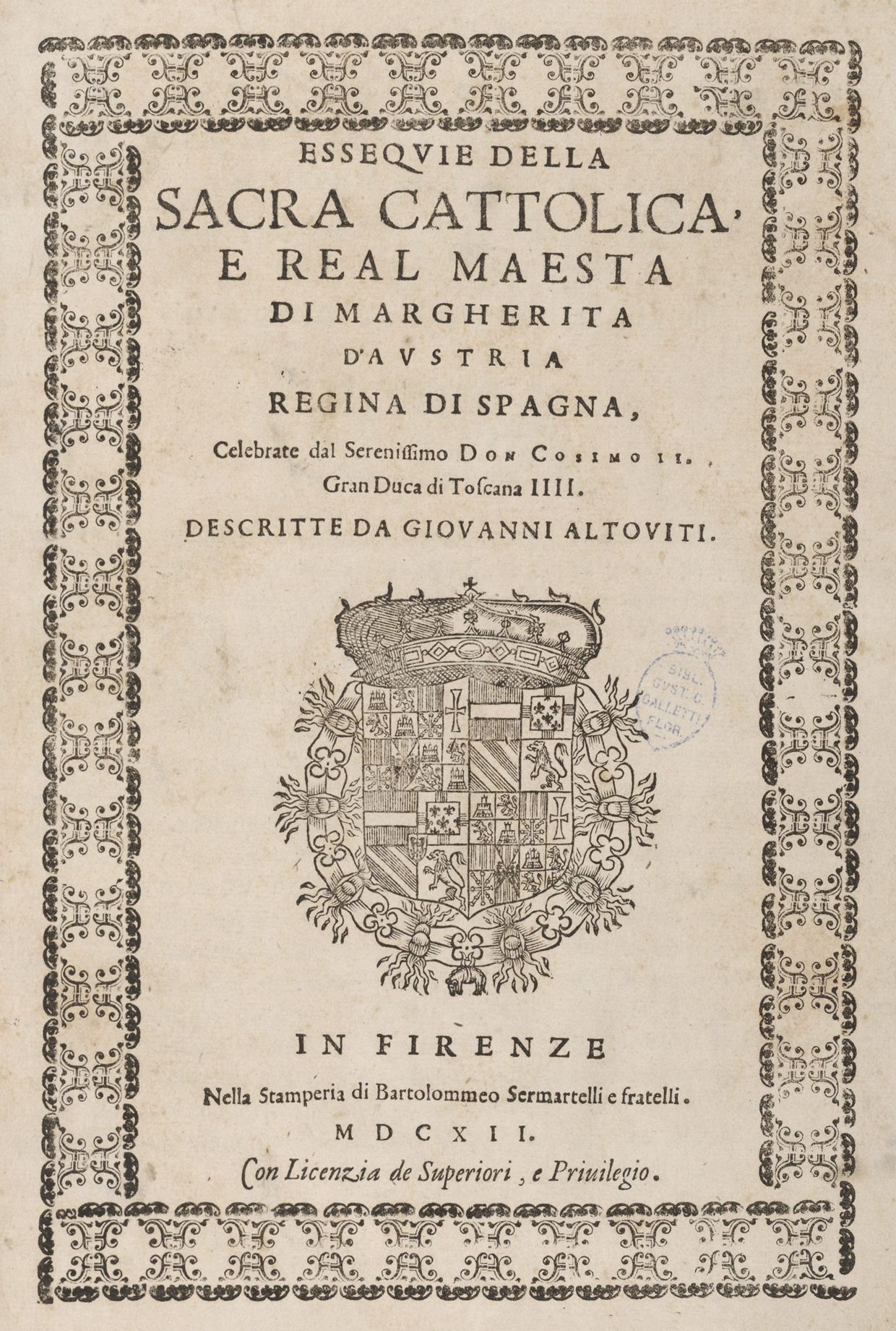

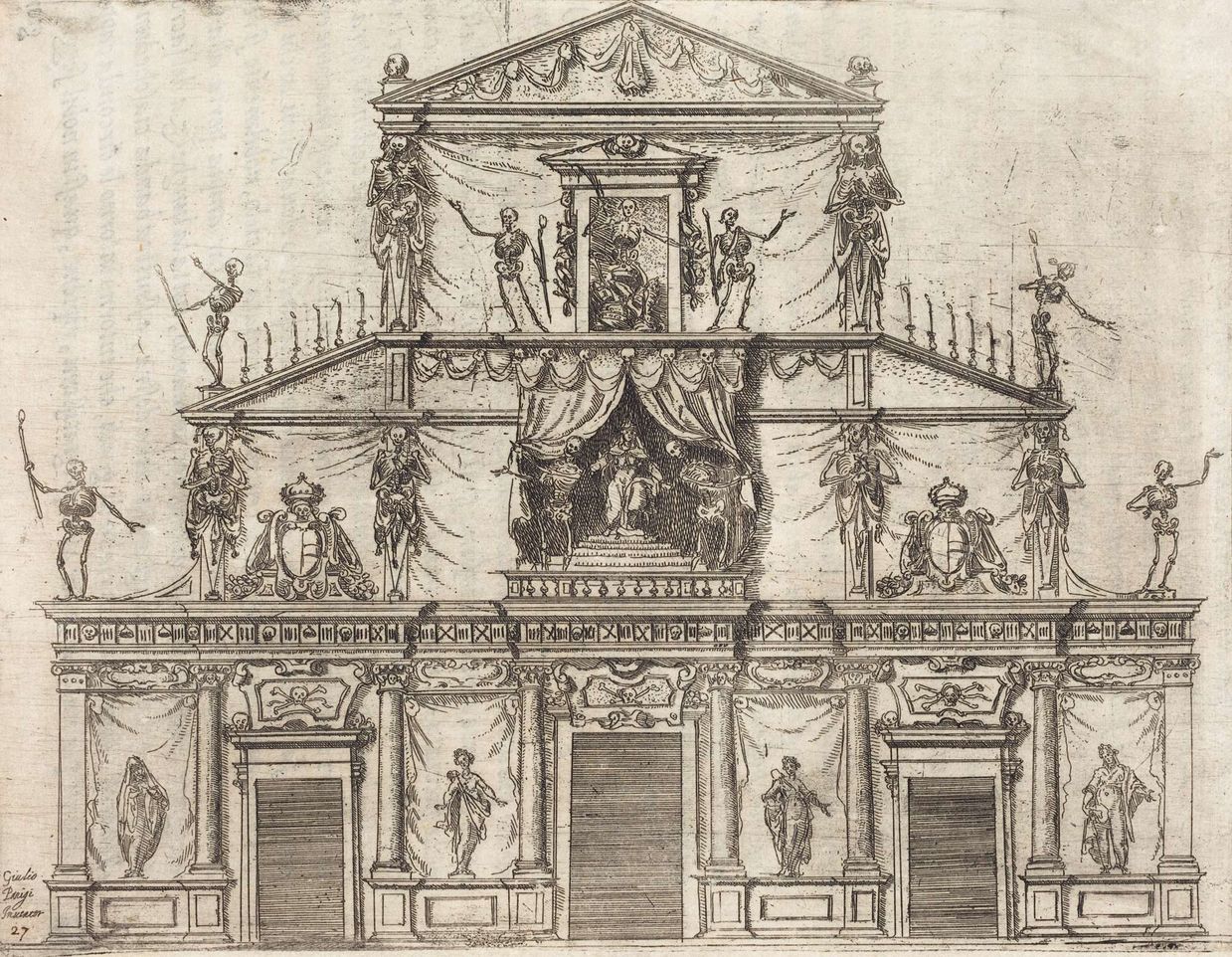

The funeral for Margaret of Austria in 1612

While the funeral of Philip II consolidates the self-representative value of effigy funerals, upon the death of Margaret of Austria, sister of the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, Maria Maddalena of Austria, an advantageous opportunity presents itself for the grand dukes to demonstrate, through homage to the deceased queen, their power and belonging.

Both funeral displays show the most relevant qualities of the two sovereigns. For Philip, we have highlighted the episodes that illustrate his greatness, his wisdom and respect for the rights of subjugated peoples. For Margaret, magnanimity, piety, and energy in defending the Catholic faith as well as her holy death are highlighted.

«Dalla cornice, che all’altezza di questo ordine imponeva fine, si sporgeva in fuora un gran baldacchino nero, con fregio ondeggiato di ravvolgiomenti di panni, che chiudendosi nella sommità, e ‘n forma di padiglione distendendosi in giù, era alzato da dua grandissime morti, le quali per questo ofizio eran poste sopra le cantonate d’un balaustrato, che sporto anch’egli in fuora, faceva ringhiera a uno sfondato oscurissimo, entro di cui in trono elevato da più gradi un gran colosso d’una statua, sopra un Appamondo sedeva, che splendidamente vestita con paludamento, scettro e corona regia, ma tutta di duolo atteggiata; rappresentava la Maestà dello Stato reale, anch’ella trofeo di morte divenuta, e nella malinconia del volto e nell’inscrizione si leggeva, che della propria condizione si lagnava. Quello splendore, che tanto le menti umane abbaglia, in un attimo oscurarsi, e quel fasto a cui gl’huomini si inchinano, ad ogni umile stato adeguarsi: CUNCTA SUBIACENT VANITATI, ET OMNIA PERGUNT AD UNUM LOCUM, DE TERRA FACTA SUNT ET IN TERRAM PARITER REVERTUNTUR (Tutto è caduco e ogni cosa conduce in un unico luogo, ogni cosa è fatta di terra e tornerà parimenti alla terra).»

From the framework, which imposed an end to the height of this order, a great black canopy projected outwards, with a frieze of waving cloths, which, closing at the top and extending downwards in the form of a pavilion, was raised by two very large figures of deaths, which for this purpose were placed above the corners of a balustrade. The balustrade, which also jutted outwards, was a railing along a very dark wall, within which, enthroned on a throne, elevated by several degrees, was a great colossus of a statue, seated on an Appamondo, splendidly dressed in a robe, with sceptre and royal crown, but all in a mood of grief; She represented the majesty of the royal state, who had also become a trophy of death, and in the melancholy of her face and in the inscription one could read that she was lamenting her own condition. That splendour, which so dazzles human minds, in a moment darkened, and that glory to which men bow, to every humble state conformed: CUNCTA SUBIACENT VANITATI, ET OMNIA PERGUNT AD UNUM LOCUM,DE TERRA FACTA SUNT ET IN TERRAM PARITER REVERTUNTUR [Everything is transient and everything leads to one place, everything is made of earth and will return equally to earth.]»

Giovanni Altoviti, Essequie della Sacra Cattolica e Real Maesta di Margherita d’AustriaRegina di Spagna, Florence, Bartolommeo Sermartelli, 1612, pp. 5–6.

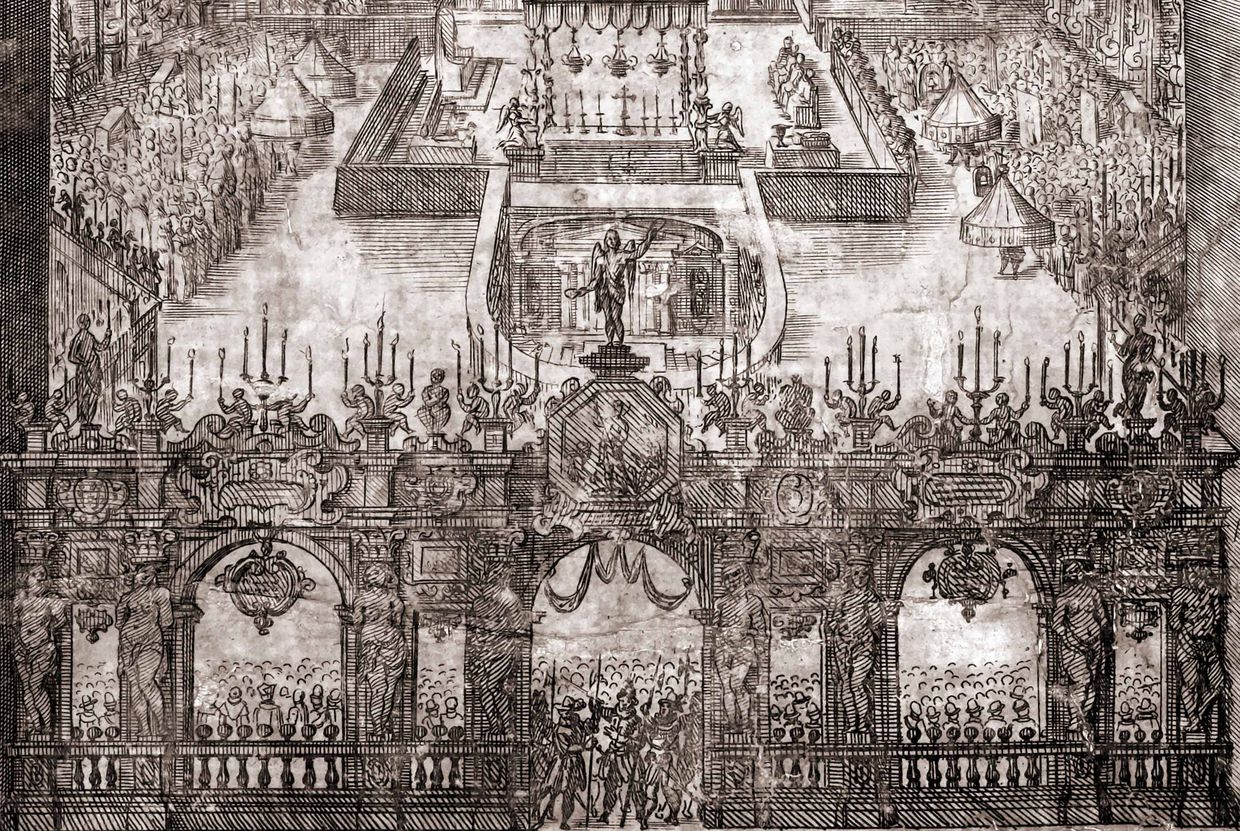

The image illustrates the apparatus on the external facade of the basilica of San Lorenzo, whose interior was once again chosen for dynastic and memorial consecration. Also on this occasion, Grand Duke Cosimo II, like his father Ferdinando I, converses with history: that of his family and of the illustrious deceased. The view of the apparatus allows us to understand the intentions of the client. Its creation was entrusted to a team led by Giulio Parigi, who at the time was the absolute master of court spectacle.

* Animations created with AI

Jacques Callot after Giovanni Altoviti, The facade of San Lorenzo, 1612. Washington, National Gallery of Art, Inv. 1969.15.281.

In this apparatus that skillfully plays with the notions of inside and outside, the action of unveiling follows the same methods as in religious celebrations: the life of the sovereign is considered the same as the life of a saint.

The life of Margaret of Austria

The episodes of Margaret’s life are chosen to guide the viewer towards evaluating the virtues of a sovereign, namely magnanimity, piety and energy towards defending of the Catholic Faith.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Giovanni Altoviti, Essequie della Sacra Cattolica e Real Maesta di Margherita d’Austria Regina di Spagna, Firenze, Bartolommeo Sermartelli, 1612.

Vincentio Pitti, Essequie della sacra cattolica real maesta del re di Spagna D. Filippo II. D’Austria. Nella stamperia del Sermatelli, In Firenze, 1598.

Secondary Literature

Monica Bietti (edited by), La morte e la gloria. Apparati funebri medicei per Filippo II di Spagna e Margherita d’Austria, Florence, Cappelle medicee, 13.3.–27.6.1999, Exhibition catalogue, Livorno, Le Sillabe, 1999.

Eve Borsook, Art and Politics at the Medici Court, III. Funeral Decor for Philip II of Spain, in: “Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz”, 40 (1969), pp. 91–114.

Juliusz A. Chrościcki, Mark Hengerer and Gérard Sabatier (edited by), Les funérailles princières en Europe, xvie-xviiie siècle, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, Centre de recherche du château de Versailles, 2015, referenced at: https://books.openedition.org/pur/116777 (18 october 2019).

Sylvène Édouard, L’Empire imaginaire de Philippe II. Pouvoir des images et discours du pouvoir sous les Habsbourg d’Espagne au XVIe siècle, Paris, Honoré Champion, 2005.

Owen Rees, The City Full of Grief: Music for the Exequies of King Phillip II, in: ”Music as Social and Cultural Practices: Essays in Honour of Reinhard Strohm” edited by Melania Bucciarelli and Berta Joncus, Woodbridge, Boydell, 2007.

Minou Schraven, Festive Funerals in Early Modern Italy. The Art and Culture of Conspicuous Commemoration, Farnham, Ashgate, 2014.

Digital resources

Paule Desmoulière, “Come ad una tanta regina si conveniva”: funérailles italiennes pour Marguerite d’Autriche-Styrie (1611-1612)”, in: e-Spania: https://books.openedition.org/pur/espania.23116 [online since 1.2.2014, visited on 7.2.2024].

Credits

| Title | Memory and Tradition. Funerals in Florence for Philip II (1598) and Margaret of Austria (1612) |

| Authors | Sara Mamone (University of Florence), Anna Maria Testaverde (University of Bergamo) |

| Origin of the images | Albertina (Vienna), Galleria degli Uffizi (Florence), Museo Nazionale del Bargello (Florence), Kunsthistorisches Museum (Vienna), Theatermuseum (Vienna) |

| English Translation | Elena Mazzoleni, Giulia Sarno, Alexander McCargar |

| English proofreading | Alexander McCargar |

| Voice | Alexander McCargar, Rudi Risatti |

Unveiling sainthood:

The 1622 canonisation ceremony in Rome

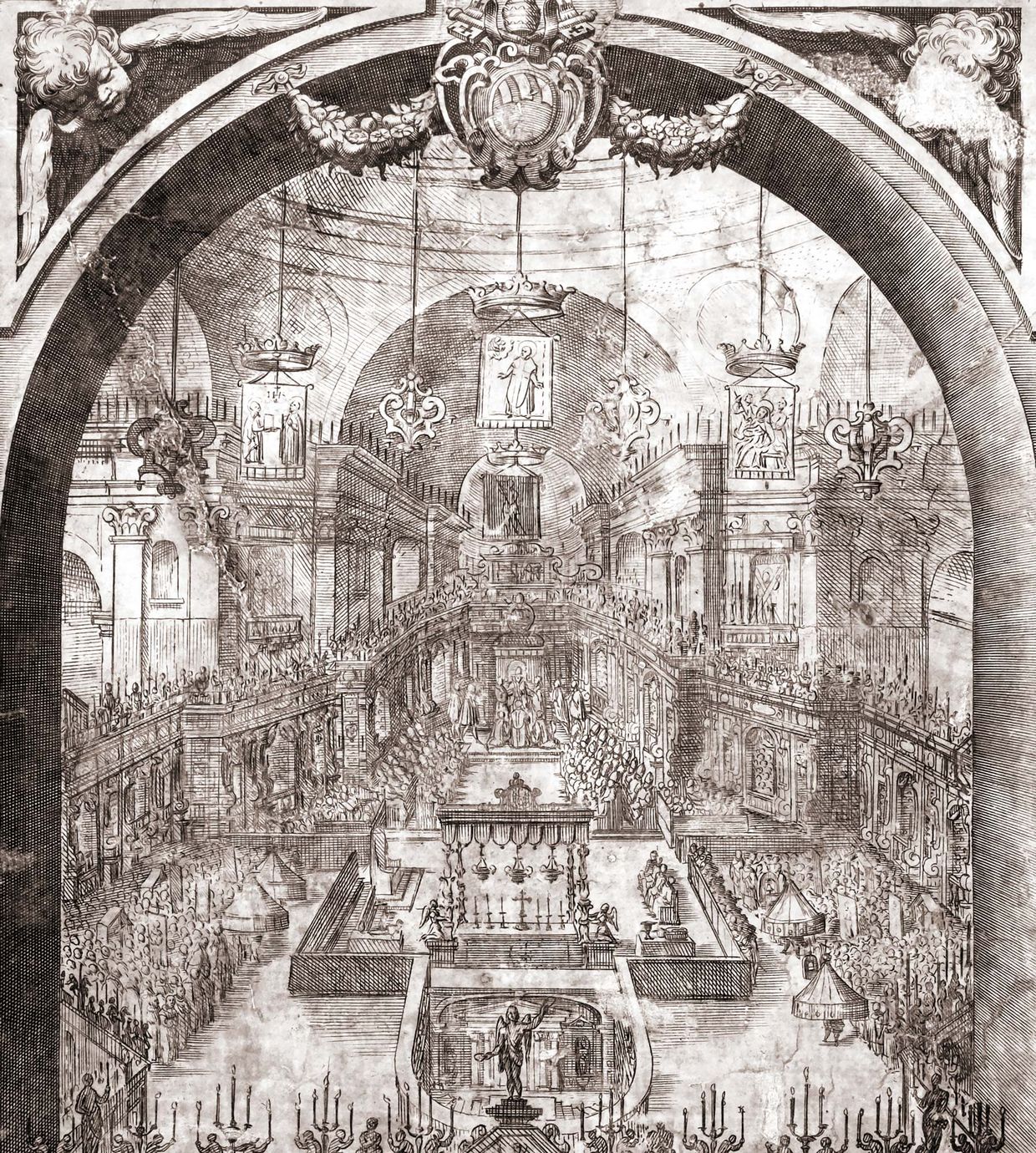

Making the invisible, the transubstantial, the symbolic, and the spiritual visible was sometimes a complicated task for the Church, but the resulting image had to reach the faithful in a clear way, and for this all the necessary instruments were used: visual, sonorous, olfactory and tactile. Approaching certain altars within a church required great ceremonies with calibrated scenographic methods developed through ephemeral architectural constructions. Eloquent images and readings, the life and virtues of newly defined heroes who had become part of the Christian orb were represented. Undoubtedly, one of the most spectacular celebrations in this sense was the one held in the Vatican Basilica in 1622, where five new saints were unveiled in a single ceremony.

The protagonists: five new saints

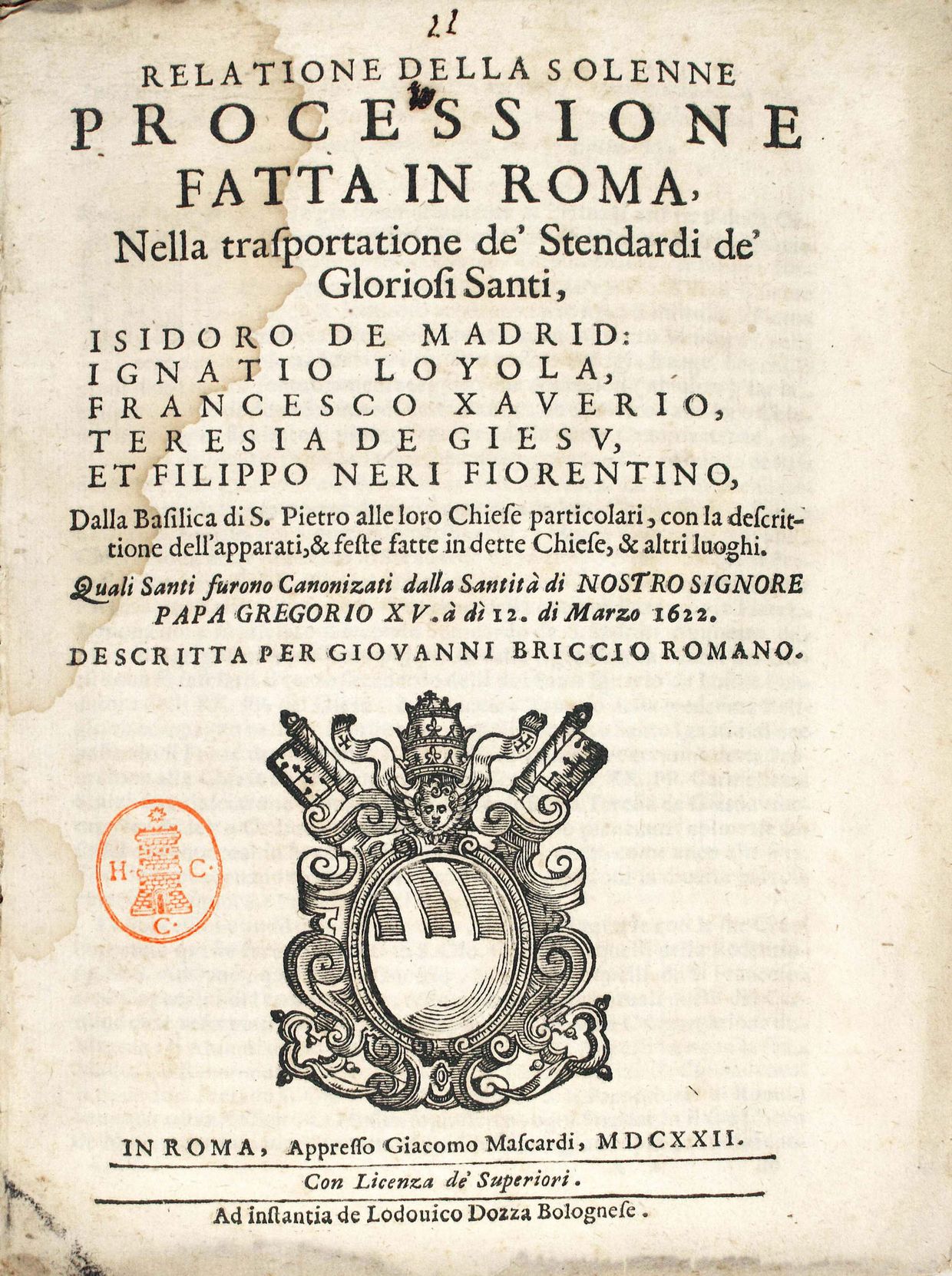

On 12 March 1622, after intense diplomatic efforts by the intermediaries of the most powerful European monarchies and the intercession and pressure of important religious orders, Pope Gregory XV, in a display of skill and subtle exercise of earthly power, canonised five new saints in a solemn, unusual and brilliant ceremony: Blessed Isidore the Laborer, Blessed Ignatius of Loyola, Blessed Francis Xavier, Teresa of Ávila and Blessed Philipp Neri.

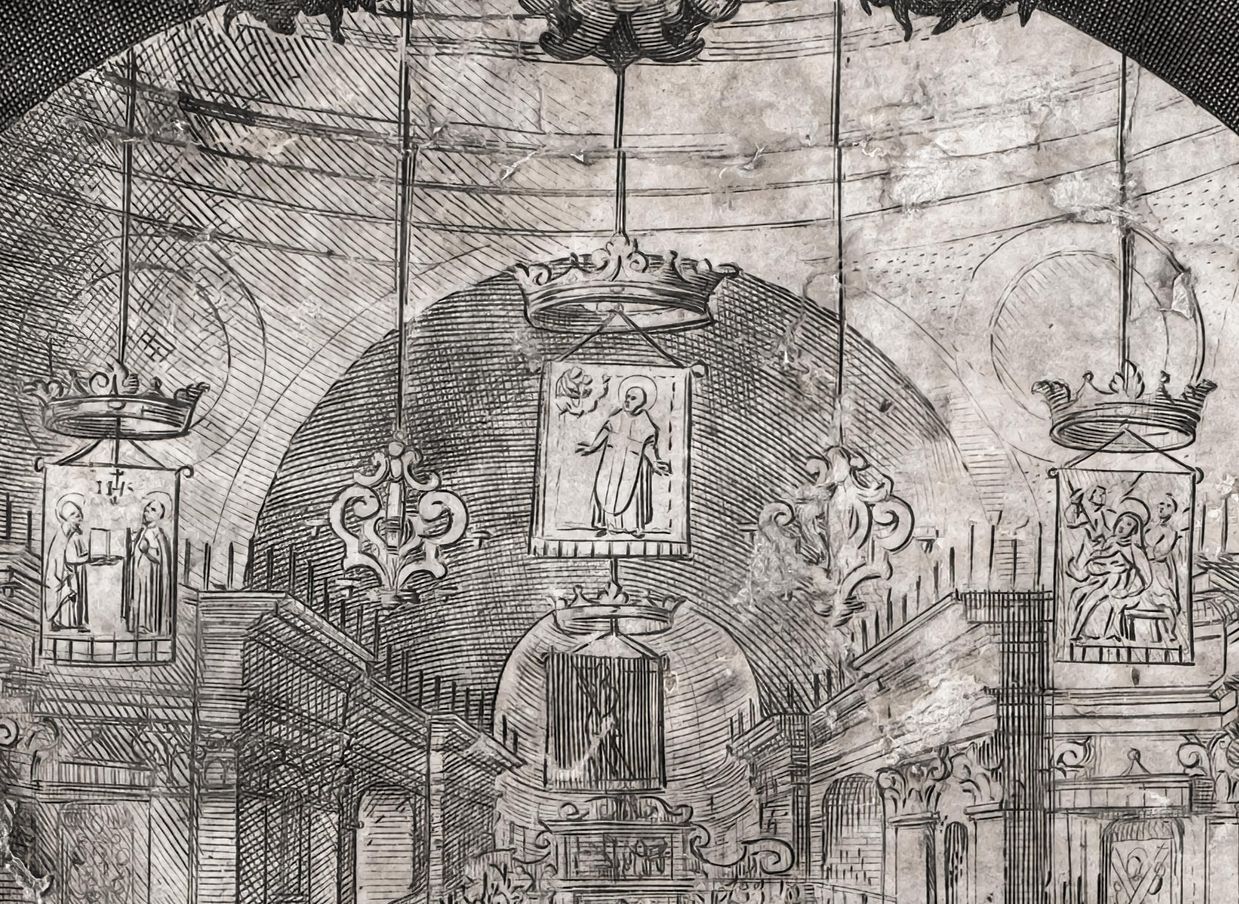

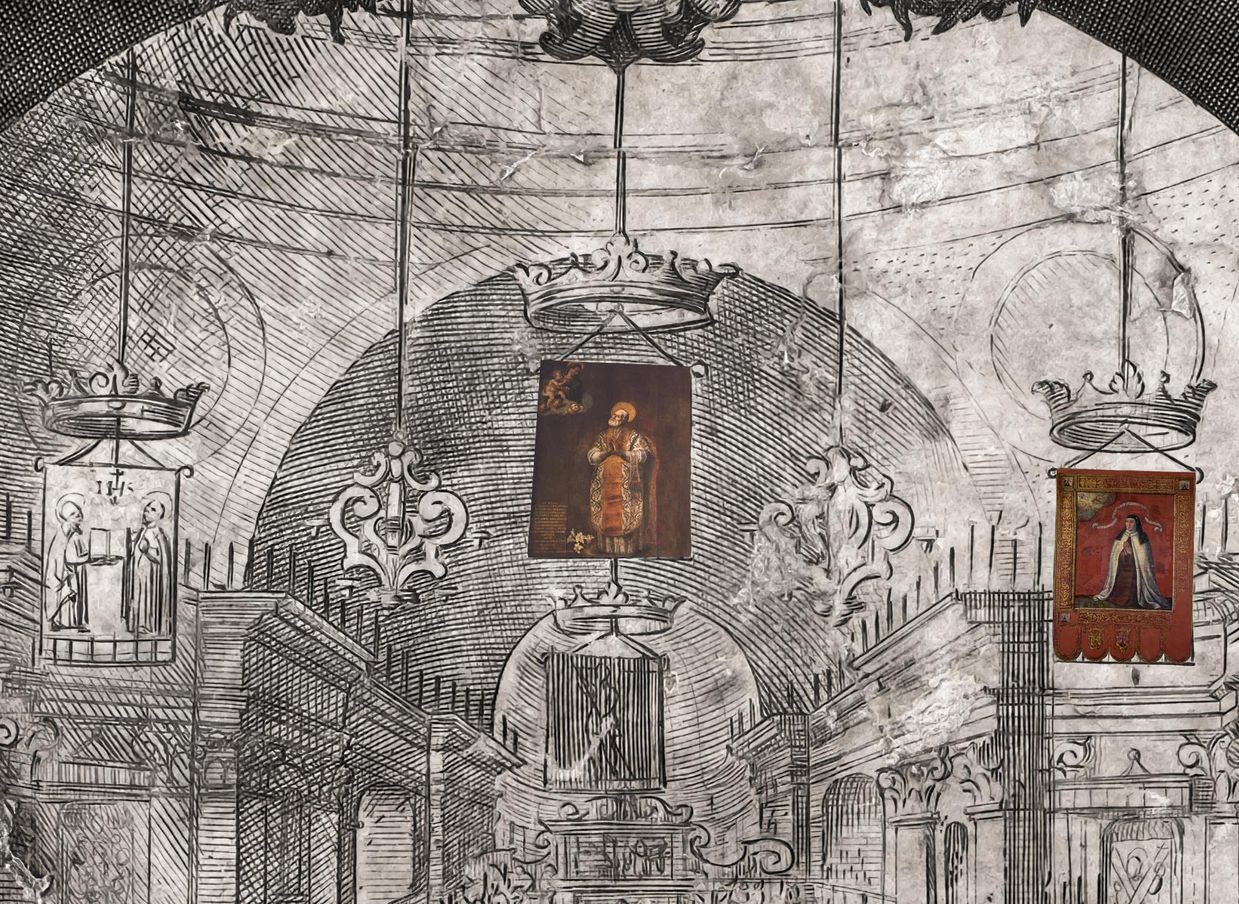

To provide a visual record of this exceptional celebration, a detailed print of the ritual by the German engraver Mathäus Greuter (c. 1566-1638) was published with a corresponding Latin cartouche. Around the central image, which shows St Peter's Basilica in the Vatican, figures of the new saints were added. They were surrounded by hagiographic vignettes summarising the most representative moments of their Christian lives.

Mathäus Greuter, Theatrvm in ecclesia S. Petri in Vaticano, 1622. Rome, Archivio della Congregazione dell’Oratorio, c.i.s., xxxvi, 4.

(Detail). Mathäus Greuter, Theatrvm in ecclesia S. Petri in Vaticano, 1622. Rome, Archivio della Congregazione dell’Oratorio, c.i.s., xxxvi, 4.

The preparations in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome: The written memory

In November 1620, at the request of Philip III and with the approval of Paul V, the canonisation of Saint Isidore began. In the summer of 1621 and following the tradition inaugurated in 1588 with the canonisation of Saint Diego de Alcalá, work began on the apse and transept area of Saint Peter's Basilica with the construction of a great scenic apparatus designed on this occasion by Paolo Guidotti Borghese, thanks to the request of the commissioner for the City of Madrid: Diego de Barrionuevo y Peralta. The memory of such an unforgettable moment was recorded – as well as in an engraving – in written sources that recalled both the preparatory work and the ceremony of such an illustrious occasion, notably in the works of Giovanni Briccio and Giacinto Gigli.

Visualising power: the Theatrum Sacrum

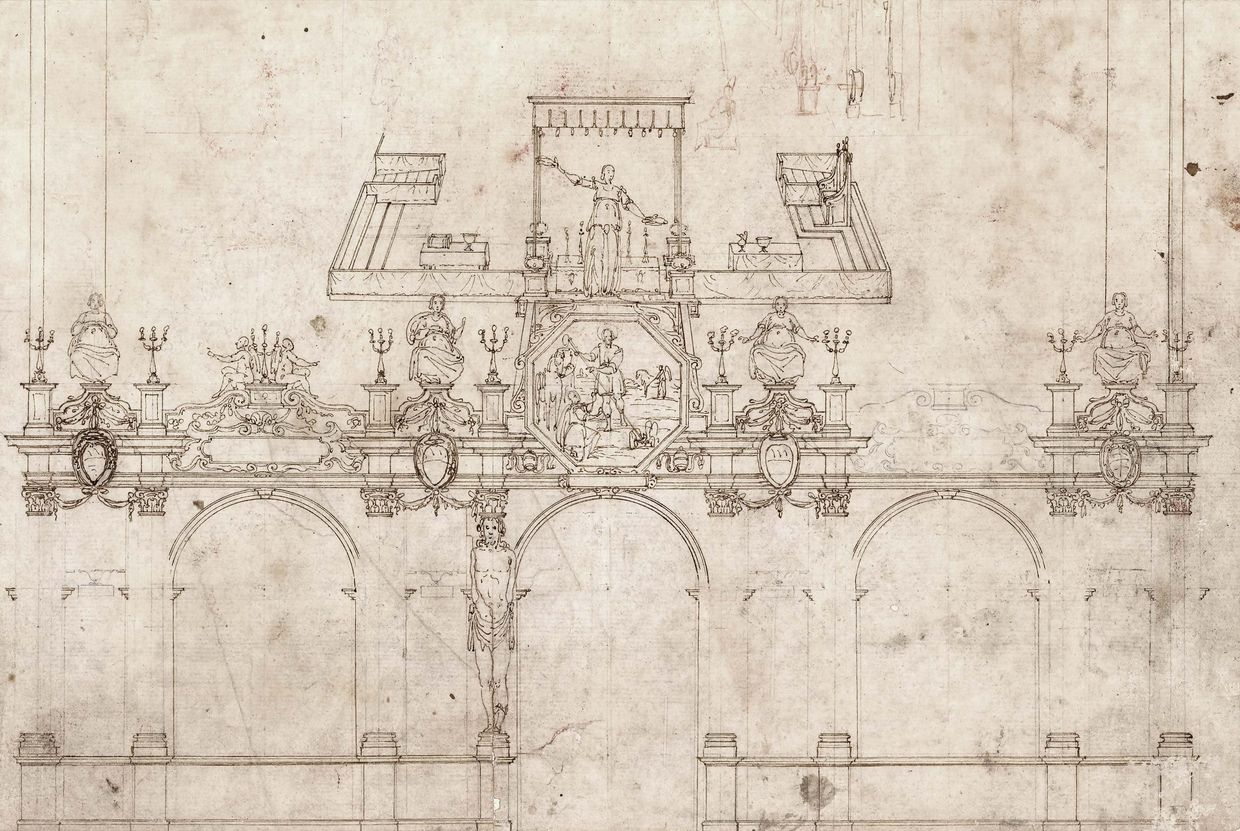

At the request of the procurator of the City of Madrid, in November 1621, Paolo Guidotti Borghese was commissioned to create an ephemeral scenic apparatus to occupy the transept of St Peter's Basilica.

In addition to the steps and side walls (richly decorated), the main façade was to be a great showcase for the symbols of the powers that had given rise to the ceremony. The figure of Saint Isidro was the main image, acting as the emblem of the city that was the main supporter of his invocation, but also the centre of the court of the Catholic king. Other eloquent symbols were the coats of arms of the King of Spain and his ambassador, the Pope and the City of Madrid, as well as scenes and allegorical figures referring to the saint. The exclusivity of the iconographic programme was due to the fact that the ceremony was originally intended solely for this saint and due to the diplomacy of the Vatican.

Paolo Guidotti, Study for the Theatrum Sacrum for the Canonisation Apparatus in Rome 1622. Vienna, Albertina, Arch. Hz., Rom, Kirchen, No. 780.

The Theatrum Sacrum

Paolo Guidotti, Study for the Theatrum Sacrum for the Canonisation Apparatus in Rome 1622. Vienna, Albertina, Arch. Hz., Rom, Kirchen, No. 780.

... erected for the lavish Baroque liturgy of the canonisation, was built with different materials, wood being the main one due to the ephemeral nature of the construction. The preparatory sketch by Paolo Guidotti Borghese shows the main façade with its magnificent arches and lintels as well as a wall which later became a balustrade, supported by pilasters that compartmentalised the surface and framed decorative and symbolic elements. The eight telamons of painted papier-mâché imitating bronze [1] were the most notable features of the final work. Above the central arch, was a canvas depicting the miracle of San Isidore making water flow from a rock [2], and on the cornice, candelabras that illuminated the construction [3]. The apparatus also contained many allegorical figures and coats of arms [4] such as that of the King of Spain, the Pope and the City of Madrid, the institution that paid for this work. On the top a figure representing Virtue completed the composition. [5]

The ceremony: Unveiling holiness

After the first rites of the ceremony, came one of the most eagerly awaited moments, that of the request for the bulls of canonisation by the Cardinal and Archbishop of Bologna, Ludovico Ludovisi, the Pope’s nephew who acted as procurator for all the blessed. His Holiness then pronounced the “Decretamus” and at that moment the silver trumpets were blown, instruments that are still used today, and artillery salvos were fired in St. Peter’s Square and Castel Sant’Angelo. This was the official act of raising the saints to the altars. Lowered banners were used as a sign of this by “unveiling” the new saints.

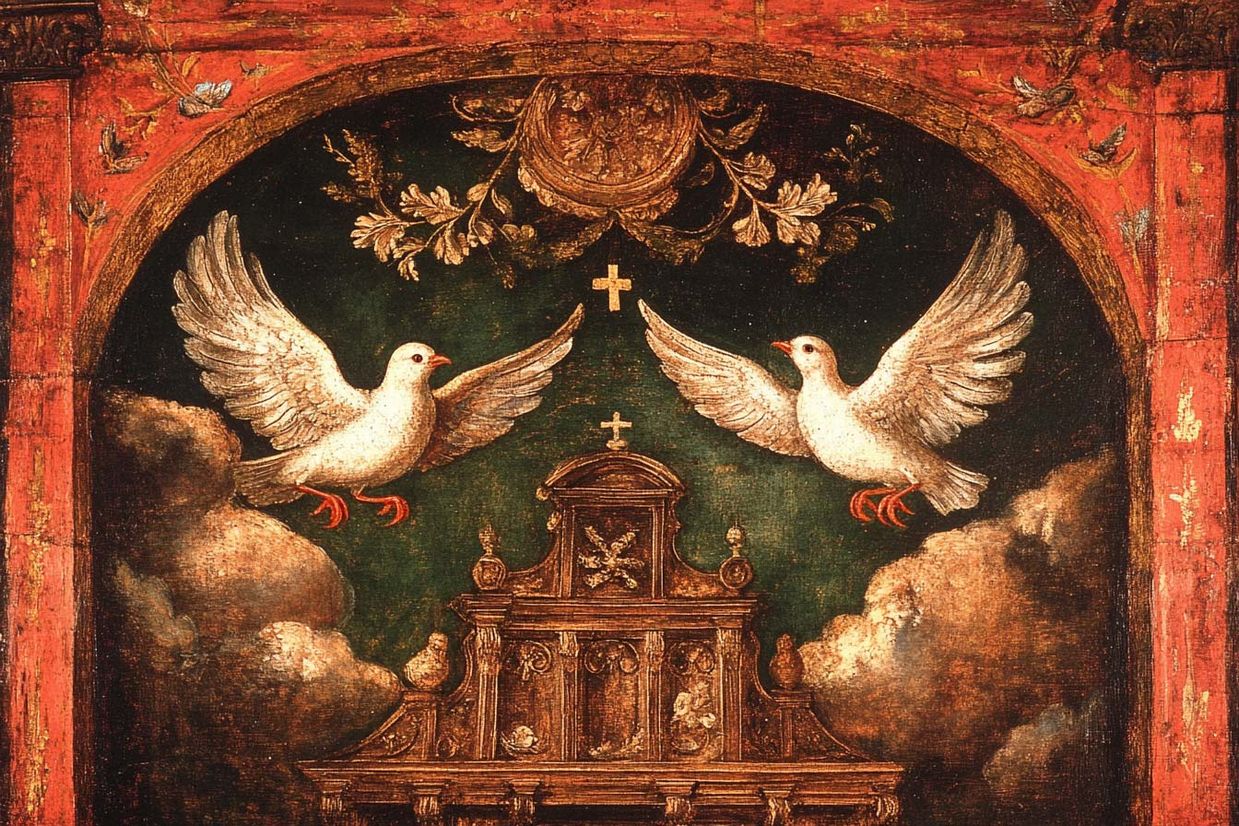

Once the Offertory was over, one of the most colourful rites took place, that is, the Offering where the promoters of the canonisations presented two candles, two large loaves of wax (one golden and one silver), two barrels of wine and two baskets with live birds (two turtledoves, two white doves and songbirds) which were finally allowed to fly before the jubilation of those present. All of this resulted in a feast for the senses.

The end of this solemn ceremony was rounded off with the ringing of the Vatican bells as a sign of joy.

Relatione della solenne processione fatta in Roma, nella trasportatione de’ stendardi de’ gloriosi santi, ISIDORO DE MADRID, IGNATIO LOYOLA, FRANCESCO XAVERIO, TERESIA DE GIESU et FILIPPO NERI FIORENTINO. Dalla basilica di S. Pietro alle loro chiese particolari, con la descrittione dell’apparati et feste fatte in dette chiese et altri luoghi. Quali santi furono canonizati dalla santità di NOSTRO SIGNORE PAPA GREGORIO XV a dì 12 di marzo 1622. Descritta per Giovanni Briccio Romano. In Roma, Apresso Giacomo Mascardi, MDCXXII.

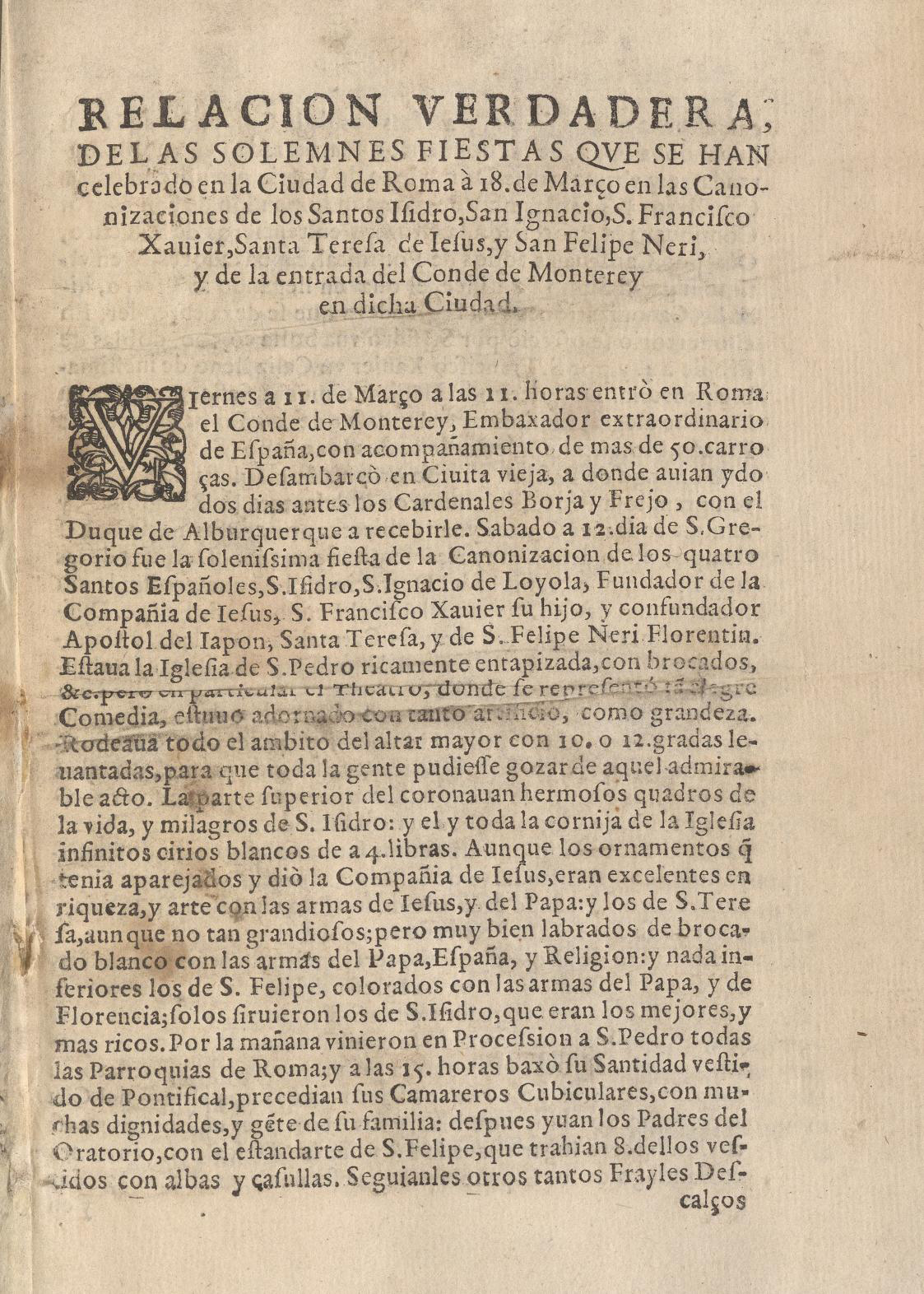

Relación verdadera de las solemnes Fiestas que se han celebrado en la ciudad de Roma a 18 de marzo en las canonizaciones de los santos Isidro [...] Con licencia, impresa en Barcelona, por Esteban Liberos, 1622.

Celebrating holiness: A multi-sensory feast

After the canonisation, solemn feasts, processions, liturgical acts, etc. were not long in coming. In these, the visual aspect of the representations was fundamental in constructing the iconography of the new saints. The churches of the Gesù, Santa Maria in Vallicella (Chiesa Nuova), of the Convento della Madonna della Scala and San Giacomo degli Spagnoli in Rome, became spaces in which the celebration gave way to multiple sensorial manifestations, as, for example, Giacinto Gigli describes in his Diario Romano. Jubilant celebrations for the new saints also took place in many Spanish cities.

Bibliography

PrimarySources

Giovanni Briccio, Relatione sommaria del solenne apparato, e ceremonia fatta nella Basilica di S. Pietro di Roma, per la canonizatione de gloriosi Santi Isidoro di Madrid, Ignatio de Lojola, Francesco Xauerio, Teresa di Giesu, e Filippo Nerio Fiorentino, canonizati dalla Santità di N. S. Papa Gregorio XV à dì 12 di marzo MDCXXII, Composto per Giovanni Briccio Romano, ad istanza di Lodovico Dozza Bolognese. In Roma, Per Andrea Fei. MDCXXII. [1622].

Giovanni Briccio, Relatione della solenne processione fatta in Roma, nella trasportatione de’ stendardi de’ gloriosi Santi, Isidoro de Madrid, Ignatio Loyola, Francesco Xaverio, Teresia de Giesu, et Filippo Neri Fiorentino, dalla Basilica di S. Pietro alle loro chiese particolari, con ladescrittione dell’apparati & feste fatte en dette chiese, & e altri luoghi..., Roma, 1622.

Giacinto Gigli, Memoria de Giacinto Gigli sobre la ceremonia de canonización...1622. Manuscrito

Anonymous, Relazione della solenne processione fatta in Roma. nella trasportatione de’ stendardi de’ gloriosi santi Isidoro de Madrid, Ignatio Loyola, Francesco Xaverio, Teresia de Giesu, et Filippo Neri Fiorentino, Roma, Giacomo Mascardi, 1622

Anonymous, Relación verdadera de las solemnes Fiestas que se han celebrado en la ciudad de Roma a 18 de marzo en las canonizaciones de los santos Isidro [...] Con licencia, impresa en Barcelona, por Esteban Liberos, 1622.

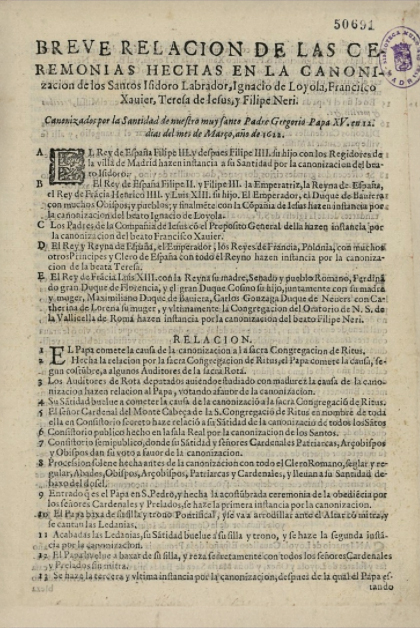

Anonymous, Breve relación de las ceremonias hechas en la canonización de los Santos Isidro Labrador [...] Con licencia, en Madrid, por Luis Sánchez, Impresor del Rey, 1622.

Alessandra Anselmi, Roma celebra la monarchia spagnola: il teatro per la canonizazione di Isidoro Agricola, Ignazio di Loyola, Francesco Saverio, Teresa di Gesù e Filippo Neri (1622), in: José Luis Colomer (ed.), Arte y diplomacia de la Monarquía Hispánica en el siglo XVII, Madrid 2003, 221-246.

Comitato Romano Ispano per le Centenarie Onoranze, La canonizzazione dei santi Ignazio di Loiola fondatore della Compagnia di Gesù e Francesco Saverio apostolo dell’Oriente: ricordo del terzo centenario XII marzo MCMXXII.

Filippo Crucitti, “GIGLIO, Giacinto”, in VV. AA. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Vol. 54. Treccani (2000). Available at: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giacinto-gigli_(Dizionario-Biografico)/ (Accessed: 12-12-2023).

Marcello Fagiolo, «Il «Gran Teatro barocco» della santità ibero-americana», en A la luz de Roma. La capital pontifícia en la construcción de la santidad. Universidad Pablo de Olavide: Roma Tre-Press. Sevilla, 2020, 19-42.

Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco y Silvia Carandini, L’effimero barocco. Strutture della festa nella Roma dell’600, Bulzoni, Roma, 1977.

Giacinto Gigli, Diario Romano (1608-1670), a cura di Giuseppe Ricciotti, Tumminelli Editore, Roma, 1958.

Pamela M. Jones, «Celebrating New Saints in Rome and across the Globe», in A Companion to Early Modern Rome, 1492–1692. Brill, 2019, 148-166.

Fermín Labarga, “1622 o la canonización de la Reforma Católica”. In Anuario de Historia de La Iglesia, 29, (2020), 73-126.

Olga Melasecchi, “Guidotti, Paolo, detto il Cavaliere Borghese”, in VV.AA. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Vol. 61. Treccani (2004). Available at: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/guidotti-paolo-detto-il cavalierborghese_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/ (Accessed: 12-12-2023).

Olivier Michel, “BRICCI (Briccio, Brissio, Brizio), Giovanni”, in VV.AA. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Vol. 14. Treccani (1972). Available at: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giovanni-bricci_(Dizionario-Biografico)/ (Accesed: 12-12-2023).

Credits

| Title | Unveiling Sainthood. The Canonisation Ceremony in Rome (1622) |

| Authors | Félix Díaz Moreno (Universidad Complutense de Madrid) |

| Origin of the images | Archivio della Congregazione dell’Oratorio (Roma), Albertina (Vienna), Museo Carmus: Monasterio de la Anunciación de Nuestra Señora, Carmelitas Descalzas de Alba de Tormes (Salamanca), Biblioteca Histórica Municipal (Madrid). |

| English proofreading | Alexander McCargar |

Sight unveiled:

Velázquez and theatre

Velázquez, in a theatrical canvas, sets the figures like actors on the stage. He shows how Apollo tells Vulcan a story he would prefer not to know. The observer takes part in the play as witness of the scene. It is a masterpiece in which its author tests the limits of art by uniting what is seen, what is known and what is remembered about a story.

The painting is read from left to right, like the text of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which it seems to illustrate, and which many educated observers would have known. In this way two different levels of reading are possible, one visual, the other mnemotechnic, as a means of showing simultaneously the mind of the painter and of the observer.

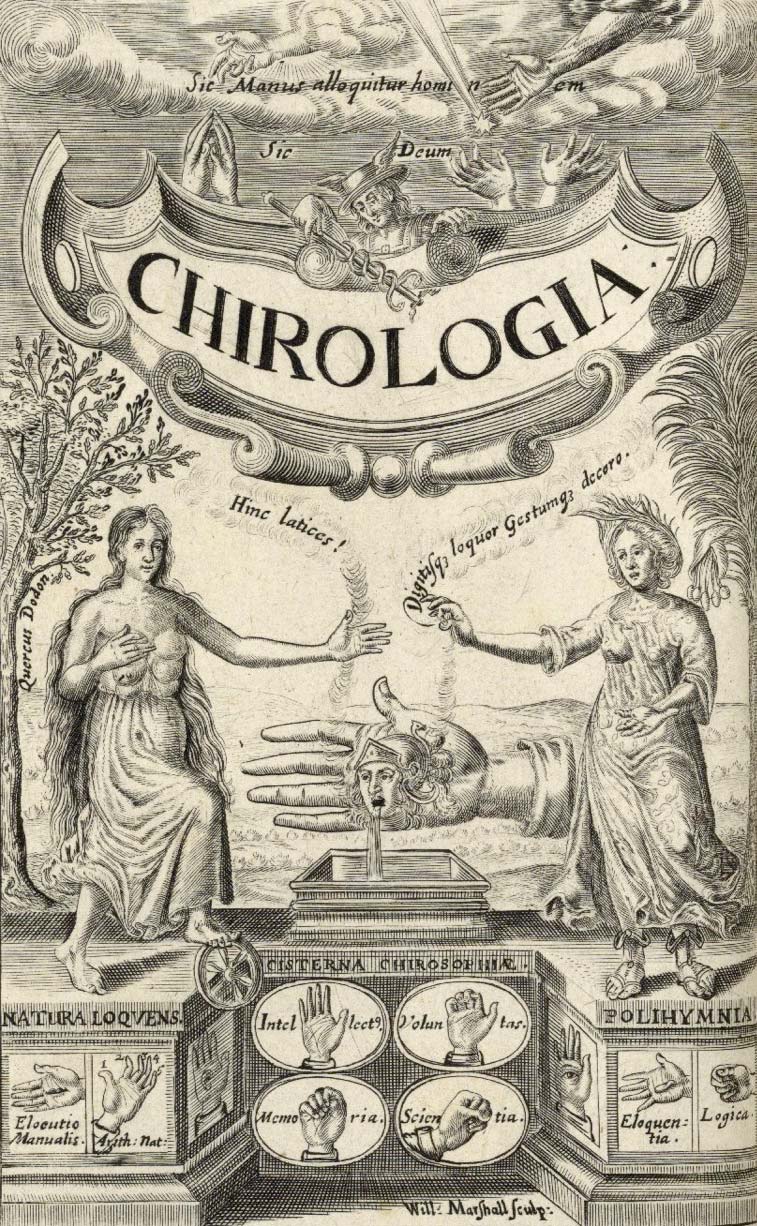

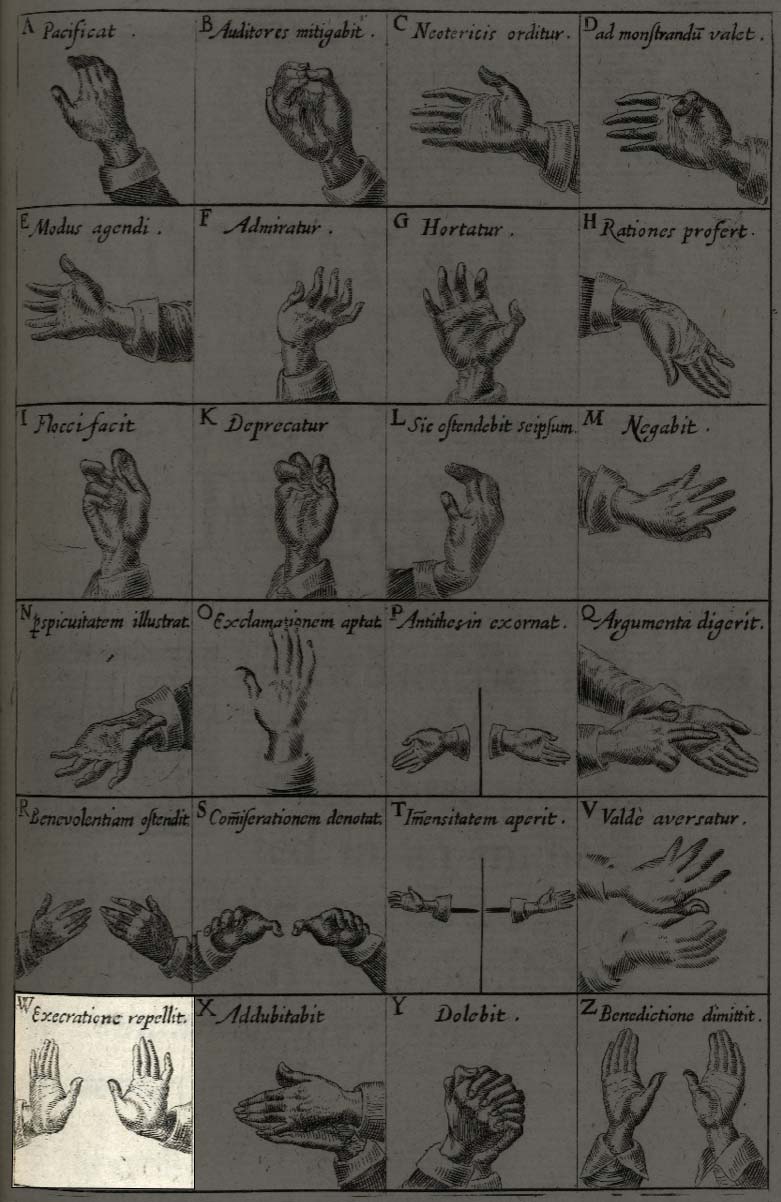

There were many accepted gestures which actors could have used, as recorded here in the book Chirologia by John Bulwer.

Velazquez shows his sense of humour by treating the original text of the Metamorphoses with some irony and a pinch of salt, adding to it a hint of embarrassment when he makes Vulcan’s dishonour a public affair by including his apprentices in the scene.

Venus, implied but not represented, becomes in this way the real protagonist of the painting, as occurs in other versions of the same subject.

Enea Vico, Venus and Mars in the Forge of Vulcan, 1543. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Antonio Pérez, Los Quinze libros de los Metamorphoseos, Salamanca, Juan Perier, 1580.

Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, Parte segunda de las comedias del licenciado don Juan Ruiz de Alarcón y Mendoza, Barcelona, Sebastián de Cormellas, 1634.

Lope de Vega, La hermosura de Angélica, Madrid, Pedro Madrigal, 1602.

Literature

Diego Angulo Íñiguez, “La fábula de Vulcano, Venus y Marte y La fragua de Velázquez”, Archivo Español de Arte, XXXIII, 1960, pp. 149-181.

Trinidad de Antonio, “La fragua de Vulcano”, Velázquez, Barcelona, Galaxia Gutenberg-Fundación de Amigos del Museo del Prado, 1999, pp. 25-41.

Jonathan Brown, Velázquez. pintor y cortesano, Madrid, Alianza Editorial, 1986, p. 72.

Carmen Garrido Pérez, Velázquez, técnica y evolución, Madrid, Museo del Prado, 1992, pp. 234-245.

Antonio Acisclo Palomino, El Parnaso español pintoresco laureado, Madrid, 1724 (Edición de Madrid, Aguilar, 1947, p. 903).

Javier Portús, Pintura y pensamiento en la España de Lope de Vega, Hondarribia, Nerea, 1999.

Santiago Sebastián, “Lectura iconográfico-iconológica de La fragua de Vulcano”, Traza y Baza, VIII, 1983, pp. 20-27.

Martín S. Soria, “La fragua de Vulcano de Velázquez”, Archivo Español de Arte, XXVIII, 1955, p. 143.

Digital resources

http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000082071&page=1

http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000171101&page=1

Credits

| Title | Velázquez and Theatre. Sight Unveiled. |

| Authors | Miguel Hermoso Cuesta (Universidad Complutense de Madrid) |

| Images provenance | Wikimedia Commons, The Internet Archive, Biblioteca Nacional de España. |

| English proofreading and voice | Alexander McCargar |

Attendite et videte

Veiling and unveiling the Glory

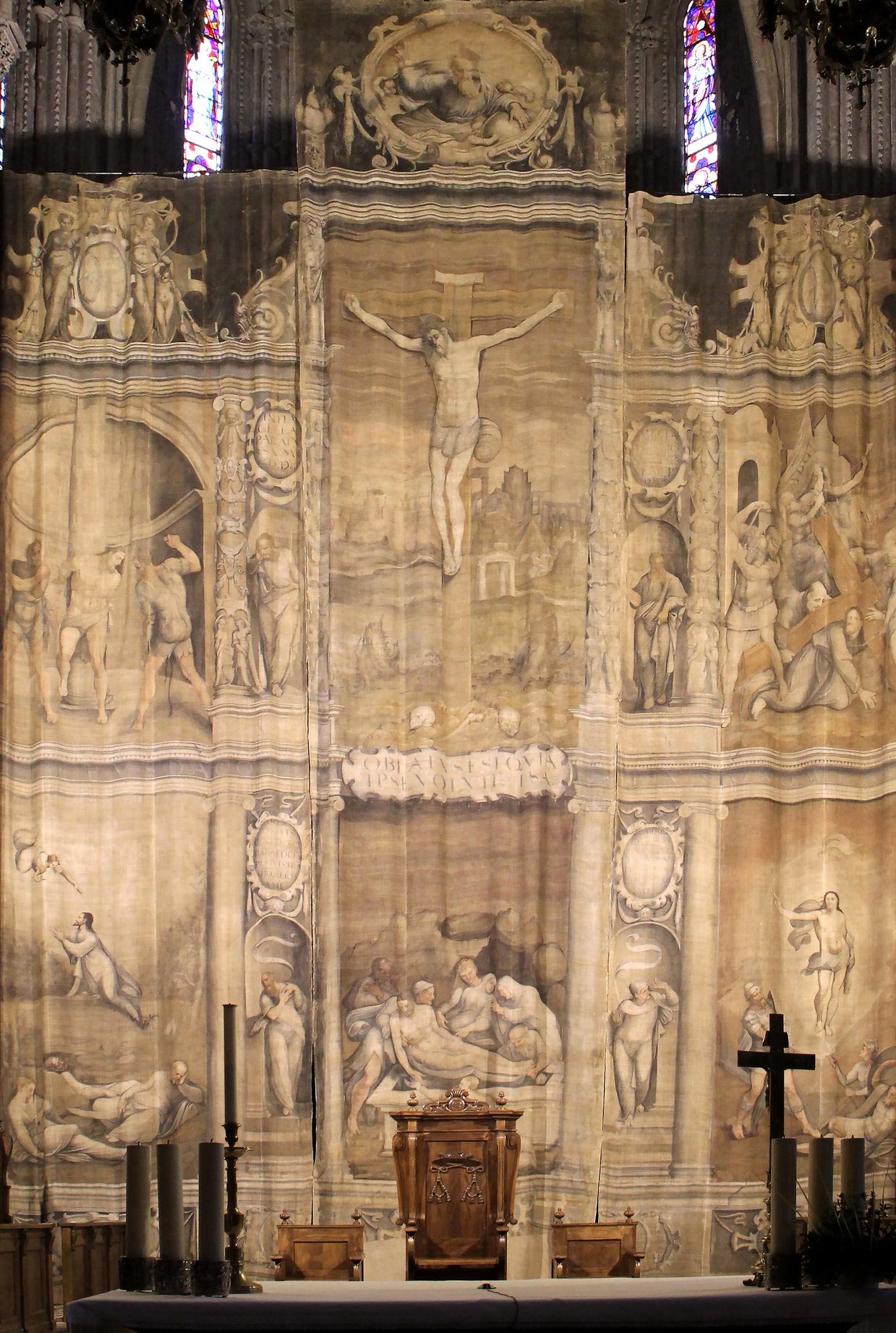

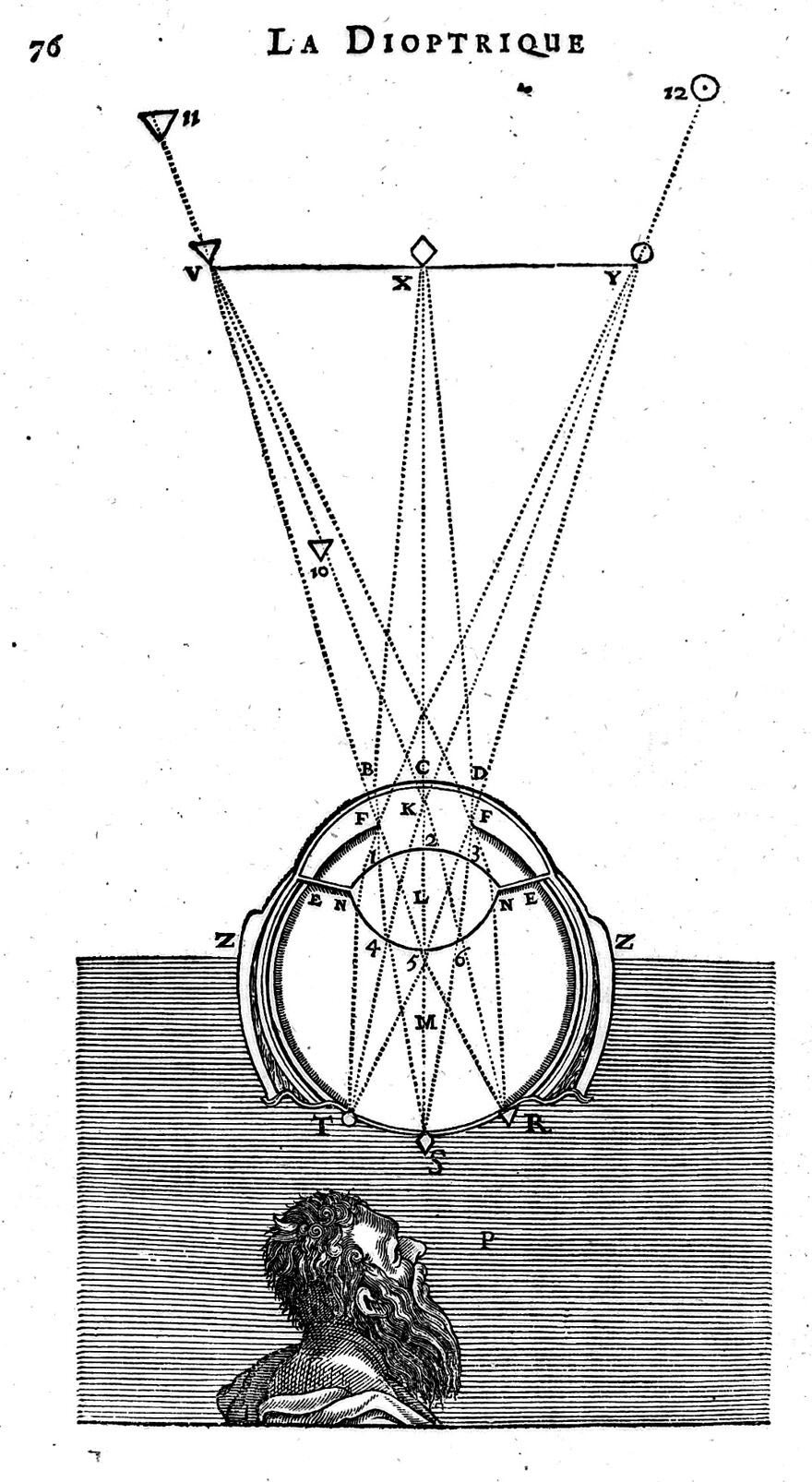

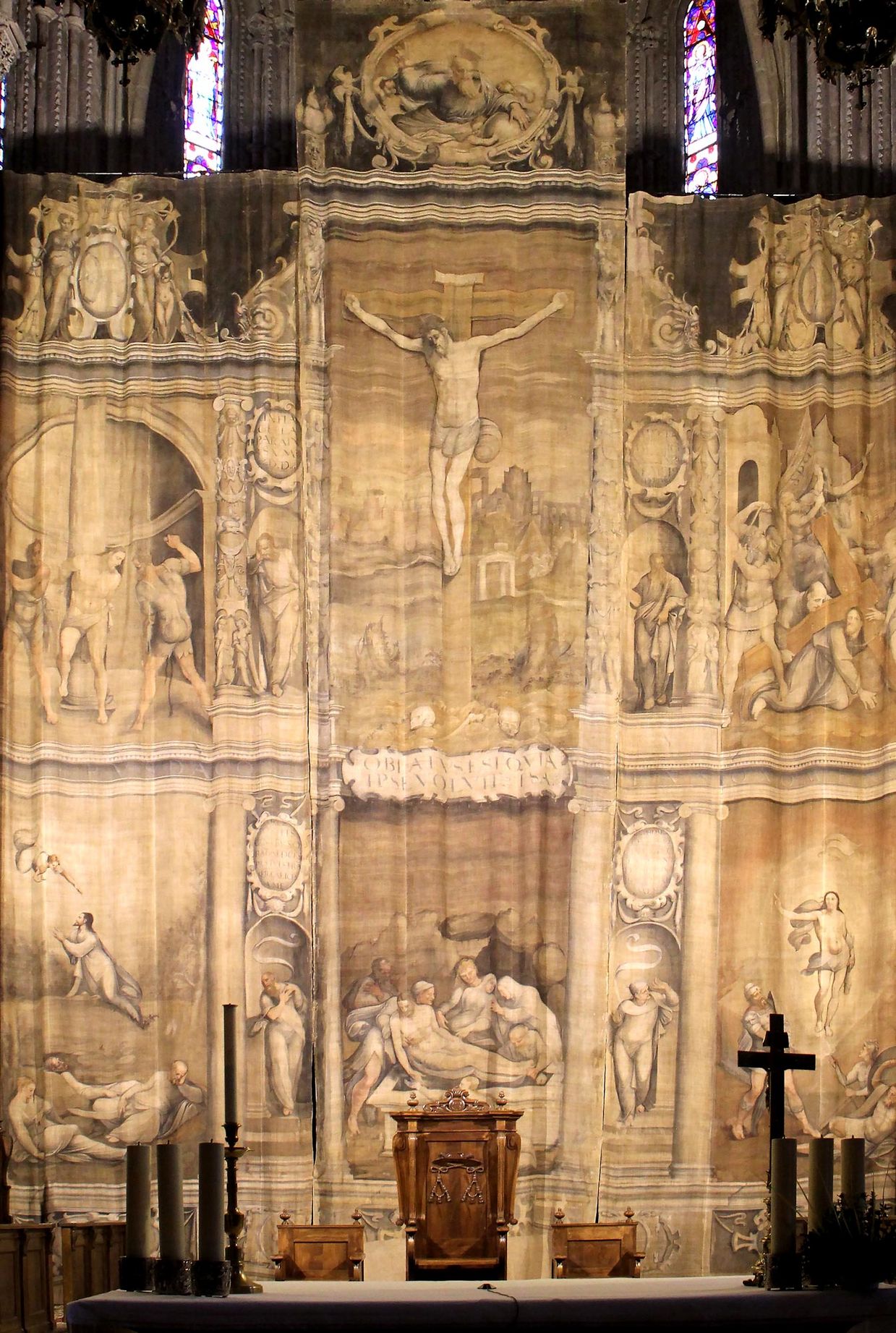

Veiling and unveiling the sacred acquires, in Christian rituals, a plurisymbolic importance. If “seeing is believing”, unveiling leads to revealing or approaching truth through sight. Passion Veils, used to hide sculptures and colourful altarpieces during Holy Week, accomplish this role and at the same time recall the veil of the Temple of Salomon, expressing the grief of Church due to Christ’s death or the awakening of sin that casts followers away from the light. Veil and altarpiece become inextricable parts of the same artistic process. Over the next few minutes, we will explain the symbolism and scenographic value of veil and altarpiece by presenting the veil preserved and still used in El Burgo de Osma Cathedral (Soria, Spain). When the veil is lowered during Christian times of glory, such as the Easter Vigil, one is able to perceive once again all the golden magnificence of the altar: a simple act of show, before our very eyes, representing the Resurrection.

O vos omnes qui transitis per viam, attendite et videte: si est dolor similis sicut dolor meus. Attendite universi populi, et videte dolorem meum: si est dolor similis sicut dolor meus.

Oh, all of you who pass by on the road pay attention and see if there is pain like my pain. Pay attention, people of the universe, and look at my pain, if there is a pain similar to my pain.

Exterior of the El Burgo de Osma cathedral

Cloth, curtain, or a simple twill, a Passion Veil was an essential pictorial typology for any Christian temple during Holy Week. The liturgy was obliged to redecorate and visually restructure a church’s interior through ephemeral means, in order to emphasise the exceptionality of Holy Week, the idea of grief, or the exaltation of the Eucharist.

Such ritualistic forms of scenography required covering altars and hiding the brightness of altarpieces and sacred images.

These veils, painted in misty and dark colours, usually represented, in trompe l'œil, altarpieces, full iconographic references to Christ’s Passion, Death and Resurrection; they played the role of the ordinary altarpiece during an extraordinary time. The veil of El Burgo de Osma Cathedral (Soria, Spain), was painted in 1557 and it is an exceptional piece, due to its age, its artistic importance and because it is one of the last veils that is still used for its original purpose. As well as the symbolic performance of the veil, the idea of veiled and unveiled sight parallels some of the essential ideas of painting and the role of the image in the Early Modern Age.

The main altarpiece of El Burgo de Osma cathedral

... is a Spanish Renaissance masterpiece. It was commissioned by Bishop Pedro Álvarez Acosta (or da Costa), Portuguese prelate, Maecenas of the arts. The creators of the altarpiece, realized between 1550 and 1554, were mainly two foreign sculptors: Juan de Juni and Juan Picardo.

The retable is entirely dedicated to illustrating the virgin Mary’s genealogy and life. It was considered, upon its creation, as “very luxurious”. Its exceptional sculptural quality is emphasized by a great scenographic sense, as shown in the central area, which shows the Dormition of the Virgin.

The Passion Veil

Such an exceptional ensemble as the main altarpiece of the El Burgo de Osma Cathedral needed a pictorial work of the same size in order to hide it at Easter. Dated 1557 – one year after the date that appears on the polychrome of the altarpiece – it was made in three large panels and measures approximately 12.5 × 10 meters. You can understand its scale in this video.

Its authorship is complex. It has been linked to the court for centuries. The most widely accepted and credible attributions are to Navarrete el Mudo or the royal painter Diego de Urbina (this second attribution is the most accepted and plausible).

The veil represents a large mock or perspectival altarpiece with a much simpler design than the wooden one, heralding the classicist evolution of altarpiece ensembles. The two sections take the form of stacked Ionic galleries with smooth shafts in the first and profuse carving in the second, replicating the columns that appear in the altarpiece it conceals.

Iconographically, the veil focuses on the Passion of Christ, revolving around the scenes of the Holy Burial and the Crucifixion. Prophets, heraldic emblems and a profuse use of cartouches with texts complete the programme, centered on redemption through the Sacrifice on the Cross.

A Passion theater

The perspectival altarpiece shows the theme of the Passion in six large scenes, giving prominence to those in the central part: the Entombment is located above the monstrance because of its connection to the Eucharist. Higher up, a large Crucifix is outlined against a backdrop of classical ruins such as the pyramid of Caius Cestius. The graphic repertoire and the references used to compose them are very varied, with echoes of Raphael and Michelangelo predominating. It is a new form that Urbina would reuse and which also exemplifies the influence of Becerra: monumental and emphatic figures that replace the simple elegance of Renaissance and the echoes of Berruguete.

The spectacle of veiling and revealing

The Catholic rite offered a rich staging during the Holy Week ceremonial, accentuating the dramatic and seeking to produce sensations and emotional and symbolic impressions in the faithful. The hegemonic role given to sight was complemented by appeals to the other senses, especially hearing and smell in those exceptional hours between the death and resurrection of Christ, between His Eucharistic presence and the tomb dug out of the rock.

The performative sensory contrasts (light/darkness, bright colours/dull tones, noise/silence), effective and simple, were perceived in a very direct way by the devotees-spectators.

Light, brightness and colour have a deep symbolism in the penitential and Easter liturgy: the darkness, the candles of the monument, the blessing of the new fire, etc. On those days, the splendour of the gold and the wide range of colours of the altarpiece were hidden by the Veil.

In this way, a symbiotic and complementary relationship is established between the veil and the altarpiece, full of symbolic games and substitutions. The curtain was conceived based on the altarpiece it covers, taking its place in the presbytery.

Finally, when the veil falls, that separated the Sancta Sanctorum, God and Glory are now present and manifested corporally before the gaze of the worshipers. Man and the capacity to see and recognize – separated from God by sin – meet again. For believers, Christ becomes evident in His Resurrection: A new alliance is made, to which humanity gains access through Jesus on the Cross and in the tomb.

After this, life returns to earth (and El Burgo de Osma) through the hope of the Resurrection.

Passion Veil falls, Video by Ramón Pérez de Castro, Year 2024, Duration: 01:50.

Bibliography

Trinidad de Antonio Sáenz, “Diego de Urbina, pintor de Felipe II”, in: Anales de Historia del Arte, 1, 1989, 141-158.

Trinidad de Antonio Sáenz, “Dos sargas de Diego de Urbina depositadas en el Parral de Segovia”, in: Boletín del Museo del Prado, 14, 32, 1993, 33-40.

Fernando Collar de Cáceres, “Diego de Urbina (1516-1595). Pintura y mecenazgo antes de 1570”, in: Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte, 22, 2010, 103-136.

Anna Muntada Torrellas, “«De la gloriosísima y purísima Madre de Dios». Claves para una lectura iconográfica del retablo mayor de la S. I. Catedral de El Burgo de Osma”, in: Llena de Gracia. Iconografía de la Inmaculada en la Diócesis de Osma-Soria, edited by Juan C. Atienza Ballano, Soria, Cabildo S.I. Catedral de El Burgo de Osma, 2005, 77-119.

Anna Muntada Torrellas, “Velo de pasión del obispo Pedro Álvarez da Costa”, in: Paisaje interior. Las Edades del Hombre. Soria 2009, 482-486.

Maestro de Osma, Veil of the Cross of Bishop Pedro García de Montoya, c. 1450-1475. El Burgo de Osma cathedral (Soria, Spain).

Collecting the Veil of Passion (Video by Ramón Pérez de Castro, Year 2024). Resurrexit sicut dixit included in the video.

Credits

| Title | Attendite et videte. Veiling and unveiling the Glory |

| Authors | Ramón Pérez de Castro (Universidad de Valladolid) |

| Images | Ramón Pérez de Castro; Diócesis y Cabildo de la S. I. Catedral de El Burgo de Osma (Soria); Fundación Las Edades del Hombre (Valladolid); Museo Nacional del Prado (Madrid). |

| English proofreading and voice | Alexander McCargar |