As ephemeral as their smells

The role of the nose in the festivities of the Early Modern Period

Carmen González-Román • Concepción Lopezosa Aparicio • Rudi Risatti • Andrea Sommer-Mathis

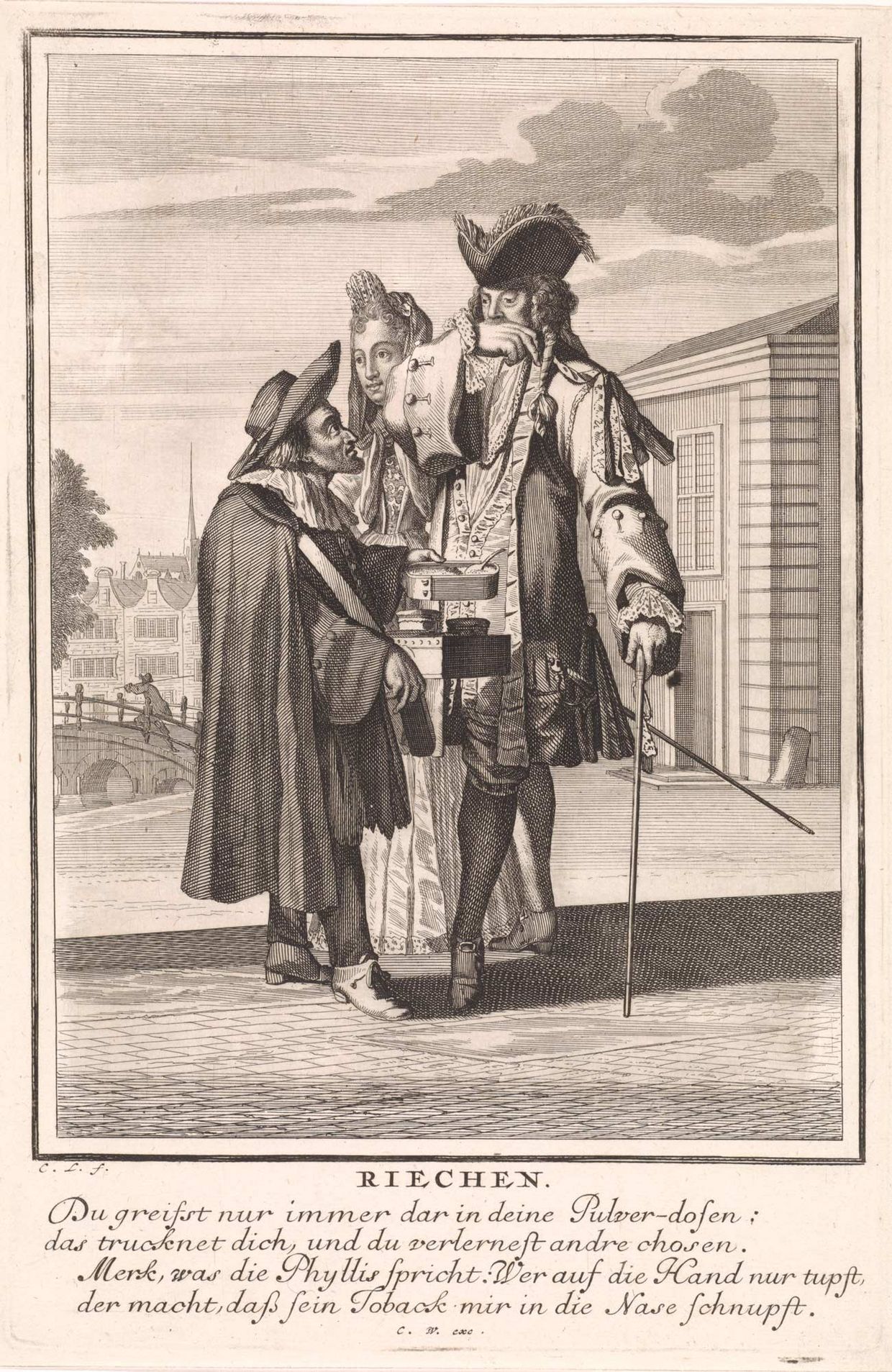

Caspar Luyken, The Smell, 1698–1702. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Inv. RP-P-1896-A-19368-1937.

* Animation processed with AI

The sense of smell is one of the first senses that human beings develop.

However, it seems to play a minor role in adulthood

Is that right

?

In the contrast between good and bad smells

many festivities of the Early Modern Period show the importance

of our nose

for cultural experiences

Animation processed with AI

A particular scent could signal how special a certain moment was

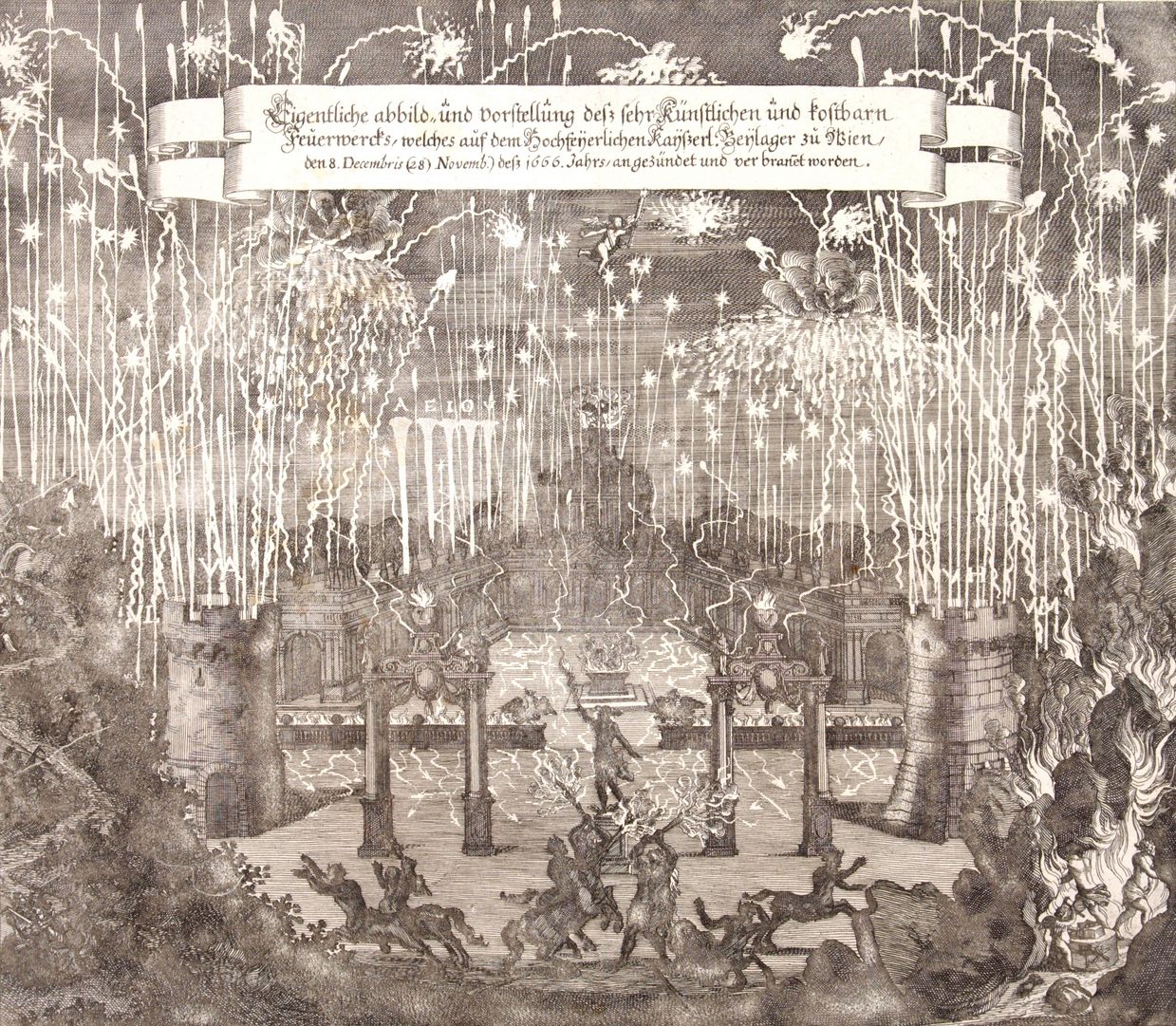

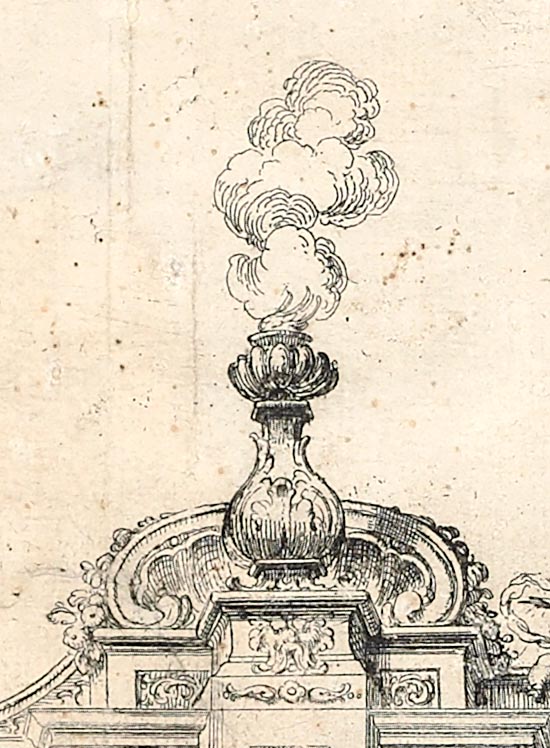

Georg Christoph Eimmart, Qui thuribulis accensa ferebant suffimenta. From: “Das große Carrosel Und Prächtige Ring-Rännen […]”, printed some time after the coronation of Charles XI in Stockholm in 1672. Vienna, Collection McCargar.

Indeed, these festivities were as ephemeral as their odours

Just think about fireworks …

Olfaction is ultimately a matter of ‘expanded scenography’ ...

in early modern festivities as well as …

Festivities en plein air

The extraordinary character of festive events en plein air was expressed through sensory means, including aromatic odours that filled the urban space and the interiors of temples and palaces, creating scents that became pure olfactory metaphors.

Religious processions in the city

The urban environment was filled with unusual odours on the days of these celebrations. Among the scents, one could smell the wax from candles, torches and candelabras.

The use of flowers and various other plants such as rosemary during celebrations in streets and squares helped to stimulate the sense of smell and sometimes even served to mask unpleasant odours from the surroundings.

Religious processions in the countryside

Incense sticks, flowers or small containers with aromatic powders were placed on the festive carriages, creating an atmosphere in which the sense of smell combined with the other senses to create a wide range of sensations.

Royal entries

Like the festive ephemeral architecture, fragrances were powerful but fleeting. The use of aromatic substances at royal festivities, such as the Royal Entry of Queen Marie Louise d’Orléans in Madrid 1680, symbolically served to create the olfactory perception of virtue and power while masking the unpleasant odours of the city on the official routes.

Street festivals

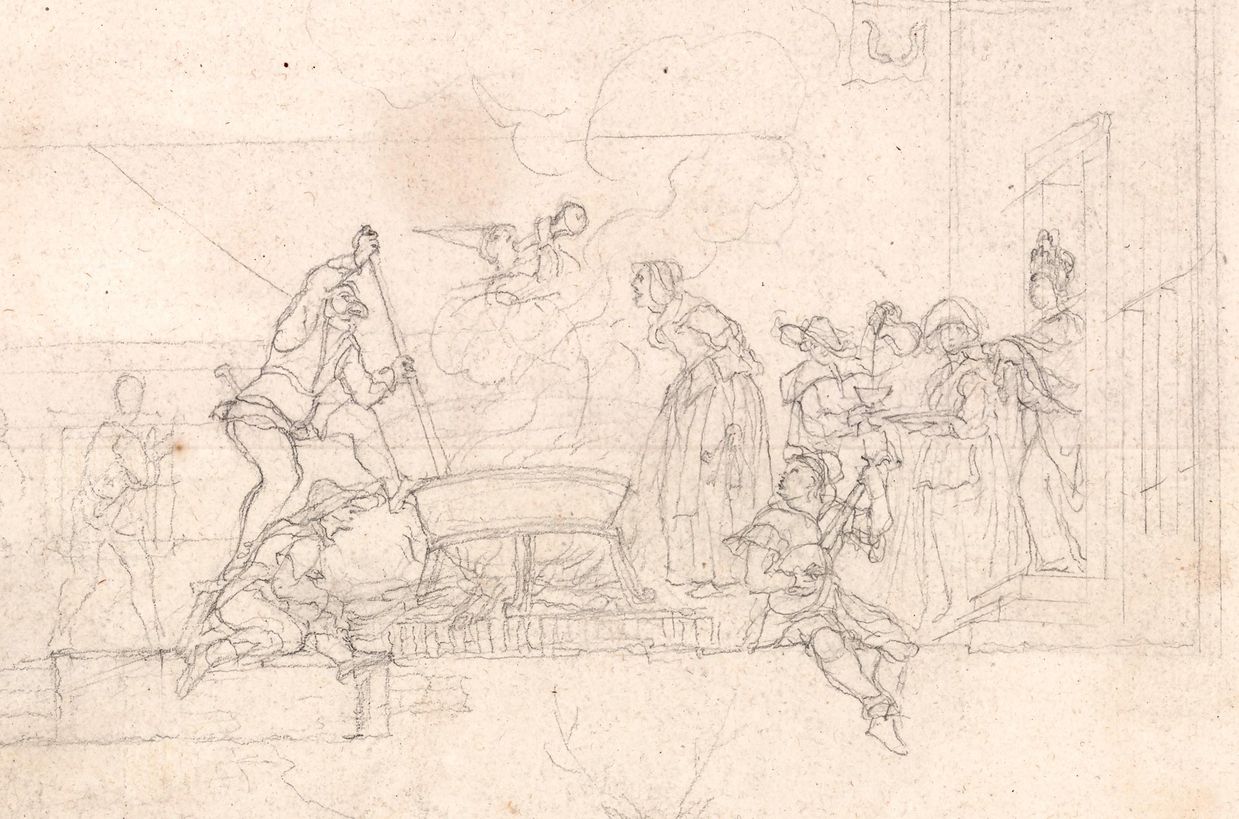

Even carnival, traditionally celebrated in the harsh winter season when fresh food was scarce, was often a festive expression of scents and flavours. The huge carnival float, pulled by the main characters of commedia dell'arte, driven by the famous Harlequin and built with all the goodness of God, is a travelling allegory of the victory of abundance over hunger ...

Could everything only be seen and tasted or even smelled?

The wheels are made of cheese, the bridle of sausage and the cart of a huge crust of bread. Are these the last remnants of the imperial larder or does it mean that there is still plenty of food left?

Of course it could also be smelled!

The odours of the festivities spread everywhere

even to places where people were excluded from the festivities.

The festive entry of Robert Dudley

This is one of twelve illustrations that were to be joined together one after the other to form a long strip. They show the festive entry of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, into The Hague on 6 January 1586, with triumphal gates and arches, scaffolds with musicians, theatres and lavish illuminations by bonfires mounted on pyramid-shaped structures with barrels, as can be seen in this plate.

Perfumed ceremonies, aromas of sanctity

Perfumes also played an important role in religious contexts.

In churches, where ephemeral catafalques were erected after the death of important personalities, the air was full of odours …

The nard: the aroma of Christ

In the past, as today, the main ingredient of the balsam used for the rite of consecration in Christianity was the essence of nard, as this was the scent with which Mary Magdalene anointed the feet of Jesus.

The importance of this and other anointings to Christianity is reflected in the Chrism Mass, a liturgical celebration of the Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran Churches in which the holy oils, used in various sacraments, are blessed.

Odours of festivities in the garden

Gardens have always played a major role in the festive tradition of the Early Modern Period. After the medieval hortus conclusus, a private place reserved for meditation, the garden opened up as a place of celebration. Its architecture, which aims to bind nature in a geometric structure, offers the opportunity to perceive the scents of plants and flowers in a systematic way.

On 6 February 1785 Emperor Joseph II hosted a festive dinner at the Orangery of Schönbrunn, with a theatre performance and a ball.

"The flowers of all seasons were fragrant here in the harshest winter on a splendid table, all around were bitter orange and lemon trees [...]."

A guest named Hieronymus Löschenkohl

In April 1622, on the Island Garden Jardín de la Isla next to the palace of Aranjuez, an exceptional setting of floral scents, La gloria de Niquea, an “invention” by Juan de Tassis y Peralta, Count of Villamediana, was performed.

“Quedaron absortos los sentidos, confessando las Ideas del ingenio más culto, que no pudieran llegar imaginadas hermosuras a la parte menor de su belleza. Desataron con aromas la Asyria y Pancaya, sin las yervas y flores, que alanbicadas vistieron de olorosa fragrancia la pureza de los aires, y como el Carro espirava rayos de visivas luzes, parecia oloroso monumento de la abrasada Fenix […]”

“The senses were absorbed, confessing the Ideas of the most cultured genius, that no imagined beauty could reach the lesser part of their beauty. The Asyria and Pancaya were unleashed with aromas, without the grasses and flowers, which, when aligned, dressed the purity of the air with intense fragrance, and as the Chariot spiraled rays of visible lights, it seemed like an odorous monument of the burnt Phoenix.”

Juan de Tassis, Count of Villamediana, Comedia de la Gloria de Niquea, y descripcion de Aranjuez, fol. 8

Smells of illness and rituals in the city

Good smells were important in the festive and religious tradition, as otherwise there were often bad odours wafting through the city and in the countryside. There was no sewage system and horses, oxen and other animals were commonly on the streets.

Because of all the dirt and filth, urban centres could be very unhealthy and epidemics could easily break out.

1679. The plague in Vienna

The plague was an extremely contagious bacterial disease that broke out very late in Vienna and other European cities.

Even in improvised hospitals it was customary to prepare fumigations

Even in improvised hospitals it was customary to prepare fumigations with rosemary or juniper essences to purify the air.

1679. The plague in Málaga

The following painting by an anonymous artist depicts the epidemic that raged in Antequera (Málaga) and other Andalusian cities in the spring and summer of 1679. Its client, the surgeon Juan Bautista Napolitano, is portrayed in each of the scenes, which simultaneously show various treatments for the disease.

The more disgusting odours of the city were mixed with others that came from different hygienic and preventive practices to disinfect and clean the environment, but also with still others linked to religious rituals.

The body – mise en scène and place of odours

When we talk about the importance of odour in the Early Modern Period, we should not only think of closed or open spaces, but also of the body itself as a carrier and producer of odours. And ...

but also in medical superstition …

in healing remedies …

“[…] unos traían un saquillo de solimán junto al corazón, pegado a las carnes, y otros debajo del brazo, unos se los quitaron porque en estas partes les causó muy grandes llagas, y otros porque sentían con él muy grandes desmayos y congojas en el corazón.”

“[…] some wore a bag of twoleaf nightshade next to their heart, attached to their flesh, and others under their arm; some took it off because it caused them great sores in these parts, and others because they felt great faintness and pain in their heart with it.”

... and in cosmetics too.

Ivory Case for Four Perfume Bottles and a Funnel, late 17th century. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Kunstkammer, Inv. 4597.

Credits

| Title | As ephemeral as their smells. The role of the nose in the festivities of the Early Modern Period |

| Coordination | Rudi Risatti |

| Authors | Carmen González-Román, Concepción Lopezosa-Aparicio, Rudi Risatti, Andrea Sommer-Mathis |

| English proofreading and voice | Alexander McCargar |

Bibliography

Historical sources

Viana, Juan de: Tratado de peste sus causas y curación, y el modo que se ha tenido de curar las fecas y carbuncos pestilentes […] Con licencia en Málaga, por Juan Serrano de Vargas y Ureña, año de 1637, Málaga 1637. https://patrimoniodigital.ucm.es/s/patrimonio/item/739360

Lobera Abio, Antonio: El por qué de todas las ceremonias de la Iglesia y sus misterios, Barcelona 1791. See especially p. 90 to 93 about wax lights and lamps in churches.

Quer, Joseph: Continuación de la flora española o Historia de las planas de España, VI, Madrid 1784. https://patrimoniodigital.ucm.es/s/patrimonio/item/650761

Rico, Don Juan: Reales exequias [...] Lima 1789.

https://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000125784&page=1

Literature

Alewyn, Karl and Richard Sälzle: Das große Welttheater. Die Epoche der höfischen Feste in Dokument und Deutung. Hamburg 1959.

Allo Manero, María Adelaida and Estban Lorente, Juan Francisco, “El estudio de las exequias reales de la monarquía hispana, siglo XVI, XVII y XVIII“. In: Artigrama 19 (2004), pp. 39-94.

Bastl, Beatrix: Feuerwerk und Schlittenfahrt. Ordnungen zwischen Ritual und Zeremoniell, in: Wiener Geschichtsblätter 51 (1996), 210–216.

Byfleet, Rose: “Plague”, in: Encyclopedia of Smell History and Heritage, accessed December 7, 2023, encyclopedia.odeuropa.eu/items/show/28. https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.10061462

Farre, Judith: “La iconografía del olor en la cultura femenina: una mirada transatlántica en cortes y conventos (siglo XVII)”. In: Bulletin of Spanish Studies, 99(2022), pp. 385–402.

Fähler, Eberhard: Feuerwerke des Barock. Studien zum öffentlichen Fest und seiner literarischen Deutung vom 16. bis 18. Jahrhundert. Stuttgart 1974.

Friess, Edmund und Gustav Gugitz: „Zur Pestperiode 1679–1680 in Wien“. In: Mitteilungsblatt des Vereins für Geschichte der Stadt Wien 1937, p. 119–122.

González-Román, Carmen: “Escenografías urbanas y recorridos sensoriales en época de epidemias (siglos XVII–XIX)“, in: Arco de sombras, Asunción Rallo (ed.). Madrid, Dyckinson 2022, p. 211–228.

González-Román, Carmen: “Los sentidos en dilatado gozo [...]”. In: Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte, 34 (2022), 31–48. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.15366/anuario2022.34.002

González-Román, Carmen y Luengo García, Francisco Javier: “Málaga 1635. Más allá de la vista [...]”. In: Francisco Ollero Lobato (Dtor.): Itinerarios urbanos y celebraciones públicas en la Monarquía Hispánica durante la Edad Moderna. Tirant Lo Blanch, Valencia 2023, 287–305.

Gugitz, Gustav: „Die Wiener Pestepidemie von 1713 und ihr Ausmaß. Ein statistischer Versuch einer Richtigstellung“. In: Wiener Geschichtsblätter 14 (1959), p. 87ff.

Hassmann, Elisabeth: Von Katterburg zu Schönbrunn. Die Geschichte Schönbrunns bis Kaiser Leopold I. Vienna-Cologne-Weimar 2004.

Iby, Elfriede (ed.): Schloß Schönbrunn: Zur frühen Baugeschichte (Wissenschaftliche Reihe Schönbrunn, 2), Vienna 1996.

Iby, Elfriede and Anna Mader-Kratky (eds.): Schönbrunn. Die kaiserliche Sommerresidenz. Vienna 2023.

Kohler, Georg (ed.): Die schöne Kunst der Verschwendung. Fest und Feuerwerk in der europäischen Geschichte. Zurich-München 1988.

Krafft-Ebin, Richard von: Zur Geschichte der Pest in Wien 1349–1898. Leipzig/Vienna: Franz Deuticke 1899.

León Vegas, Milagros: “Arte y peste [...]”. In: Boletín de Arte, 30-31, 2009-2010. Disponible en: https://www.uma.es/media/files/BA3031.pdf

Lotz, Arthur: Das Feuerwerk. Seine Geschichte und Bibliographie. Leipzig s.a. [1940].

McKinney, Joslin & Palmer, Scott: Scenography Expanded. London, Bloomsbury, 2017.

Mínguez, Víctor e Inmaculada Rodríguez Moya: “Un imperio iluminado [...]”. In: Visiones de un imperio en fiesta. Fundación Carlos Amberes, Madrid 2016, 9–29.

Morales, José Miguel. “Los túmulos funerarios de Carlos III [...]”. In: Boletín de Arte, 9, 1988, pp. 135–158.

Mutschlechner, Martin: Schloss Schönbrunn (Die geheime Geschichte [...]), Vienna 2012.

Olbort, Ferdinand: Die Pest in Niederösterreich von 1653 bis 1683. Ph.D. ms., Vienna 1973.

Olbort, Ferdinand: „Vergessene Pestjahre [...]“. In: Wiener Geschichtsblätter 28 (1973), S. 10ff.

Patzer, Franz (ed.): Die Pest in Wien – 300 Jahre lieber Augustin. Vienna 1979.

Pölzl, Michael: „In höchster Not – Der Hof in Krisenzeiten“. In: Kubiska-Scharl – Pölzl: Das Ringen um Reformen. (Mitteilungen des Österreichischen Staatsarchivs 60/2018), S. 231f.

Reinarz, Jonathan: “Hospitals”, in: Encyclopedia of Smell History and Heritage, accessed 7 December, 2023, encyclopedia.odeuropa.eu/items/show/6. 123445/5.6969.

Risatti, Rudi (ed.): Groteske Komödie in den Zeichnungen von Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini. Vienna 2019.

Schmölzer, Hilde: Die Pest in Wien. Berlin 1988.

Schöne, Günter: „Barockes Feuerwerkstheater“, in: Maske und Kothurn 6 (1960), 359f.

Schumann, Jutta: „Die Hochzeit mit Margaretha Theresia 1666/67 [...]“. In: ead.: Die andere Sonne. Berlin 2003, 243–254.

Sommer-Mathis, Andrea: „Höfische Repräsentation in Theater und Fest [...]“. In: Gruber and Mokre (eds.): Repräsentation(en). Vienna 2016, 131–149.

Tassis, Juan de, Conde de Villamediana: Comedia de La Gloria de Niquea [...]. In: Chaves Montoya (ed.): La gloria de Niquea. Aranjuez 1991.

Tullett, William: “Rosemary”, in: Encyclopedia of Smell History and Heritage, accessed 7 December, 2023, https://encyclopedia.odeuropa.eu/items/show/11.

Tullett, William: “Incense”, in: Encyclopedia of Smell History and Heritage, accessed 19 December, 2023, https://encyclopedia.odeuropa.eu/items/show/11.

Velimirovic, Boris and Helga: “Plague in Vienna”. In: Reviews of Infectious Diseases 2 (1989), Nr. 5 (Sept.–Oct.), S. 808ff.

Verbeek, Caro: “Eau de Cologne”, in: Encyclopedia of Smell History and Heritage, accessed 7 December, 2023 https://encyclopedia.odeuropa.eu/items/show/34.

VV.AA. El arte de la belleza, catálogo de la exposición. Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, 2011.

Zapata, Teresa: La entrada en la Corte de Maria Luisa de Orleans. Madrid, 2000.