Between Heaven and Earth

Spirituality and materiality of touch

Isabel Alba • Felipe Serrano

Ritual and tactility

Is touch only physical or does it have a spiritual aspect?

Touch is the sense directly linked to the act of creation.

Touch is the sense with which we perceive the physical qualities of surfaces.

Touch is the receptor of pain.

Touch is the receptor of caresses.

For the unbeliever, touch can be the union of the earthly plane with the celestial divinity.

How does the ritual of touch work?

The physical world enters our consciousness through the hand. The voluntary movement of the fingers is the ritual that leads to haptic awareness.

By the exploratory ritual that we actively or passively perform with our fingers, human beings perceive and come into contact with the materiality of the environment and other beings.

Thanks to the haptic sense we believe in the physical existence of what we touch.

This is why touch can be interpreted as a bridge between heaven and earth.

Thomas required physical contact with Jesus’ wounds to believe in his resurrection: “Reach your finger here, and look at My hands; and reach your hand here, and put it into My side. Do not be unbelieving, but believing” (John 20:27).

But how does touch work?

Touch communicates the materiality of an object or being, allowing us to perceive shape and volume and to recognize the characteristics and poetics of surfaces: smoothness, roughness, ductility and temperature. Through it we appreciate caresses or perceive physical pain.

In fact, touch connects us with the world through sensation, enabling us to feel, recognise and remember reality, even beyond the illusions perceived by the eye. On the other hand, the other senses can activate tactile perceptions even without a physical touch.

Thanks to touch we feel everything that surrounds us. It guides our imagination.

Every artistic manifestation has tactile qualities that define it and that invite us to imagine its tactility.

The organ of touch, our skin, not only touches, it is also touched itself, for example by the fabrics covering the body, causing different sensations.

* Animation created with AI

Image created with AI

How does the virtual world suggest textures?

How does today’s highly technological society affect the sense of touch?

New technologies place ever greater demands on our sense of sight. However, this also leads to a kind of 'visual pollution'. The reduction in physical contact can also damage our haptic memory.

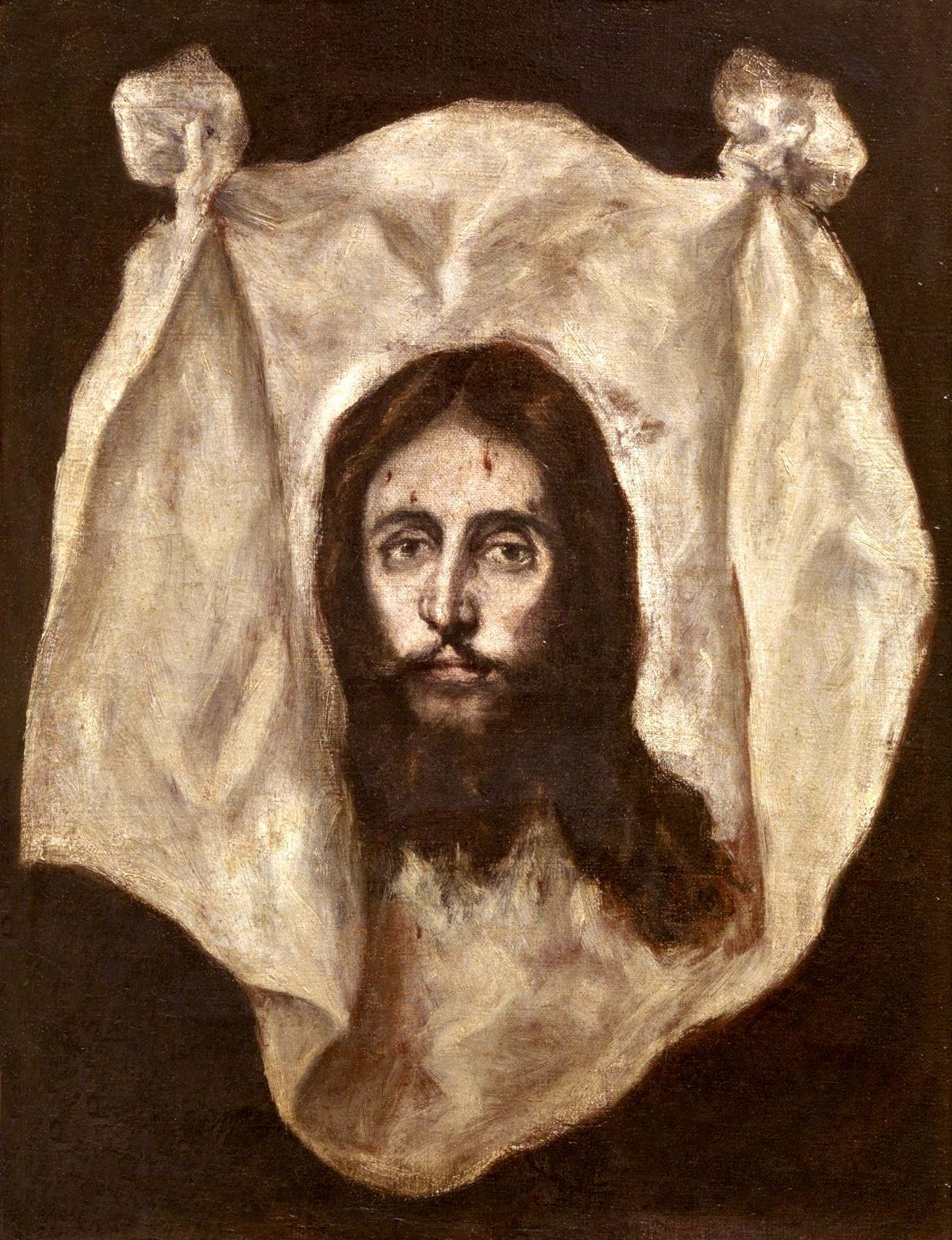

Touching the sacred: the Holy Face of Jaén

As we have seen, touching implies recognizing something or someone. In this tour we are going to investigate a cult in which touch played and still plays a major part.

Direct contact with the divine

The desire to touch relics, or at least to be close to them, has been constant throughout history.

Their thaumaturgical and protective properties, as well as closeness to the values and ideals they represented, encouraged this interest. But touching was not always possible and this limitation increased the desire for closeness.

The relics of the Passion

This desire to touch was greater if the relic came from Christ himself, and even more if it had been obtained during an important episode in his life such as the Passion. Desire grew as well if a relic came into being without human intervention, as was the case with the acheiropoieta.

These were the products of a miraculous event. Outstanding among the acheiropoieta of the Passion were the Holy Shroud of Turin, the Sudarium of Oviedo and the Veils of Saint Veronica.

What were the Veils of Saint Veronica?

According to tradition, three portraits of Christ were imprinted on the Veil of Saint Veronica. One was said to be in Rome, the other, more doubtfully, in Jerusalem, and finally there was the one that concerns us, in Jaén Cathedral.

These portraits were considered to be of great symbolic value, as they came directly from Jesus.

These ‘traces’ of Christ made his presence more real. In the first half of the seventeenth century, following the declarations of Cardinal Baronio, Bartolomé Ximénez Patón recalled that Christ left tokens “of his divine humanity” which served as consolations or remedies for those who came close to them (Ximénez Patón, 1628, p. 42).

The Holy Face of Jaén

The preservation of some relics of such high importance in Spain, which would normally be found only in Rome or the Holy Land, made it possible for the faithful to have access to them. So it was at Jaén Cathedral with the reliquary of the Holy Face.

Thousands of pilgrims came to the city from all over the world not only to see but also to touch the “true portrait” of Christ.

The ostension

The relic is solemnly displayed twice a year on Good Friday and the day of the Assumption of the Virgin, 15 August, the feast day of the cathedral’s dedicatee.

During the Early Modern Period, the Holy Face was taken to the high altar and then to the upper galleries, from where it was presented to the faithful from the balconies of the cathedral. These balconies were adorned with heraldic banners and each given two large lit wax candles. Before bringing out the relic, the acolytes lit incense as well. It was the bishop, and in his absence the dean, who displayed the relic. They were accompanied by priests, while from the balconies nearest the one on which the ostension took place the acolytes announced its arrival. Litanies were sung, which were audible nearby, thus influencing the urban space.

Apart from these two dates, the cult of the Holy Face has revolved around the place where it is kept: the chancel.

The ostension of the Holy Face on the 5th August 2023 in Jaén. Photo: © Catedral de Jaén.

A ceremony for the senses

The ceremony of the ostension of the Holy Face stimulated all the senses. The pilgrims who came to see the relic smelled the incense with which it was worshipped, listened to the litanies and the music that solemnised the celebration, and in addition, as something exceptional that did not usually occur in ceremonials created around other relics, they could touch it, kiss it and pass sacred objects over it.

Sight

Even from a great distance, as early modern sources emphasised, the relic could be seen very clearly. The humanist Ximénez Patón (1569–1640) stated that one of the miracles of the Holy Face was

“que viniendo tanta gente a vella, nadie se va descontento de avella visto, porque aunque más distantes se pongan la ven con la distinción y certeza, que los que la miran muy cerca y así ha sucedido y sucede, que por muchos no caber en la plaça ni en contorno de la Santa Iglesia por cuyas ventanas la va mostrando a la gente devota el obispo, o en su ausencia el deán, se suben a açoteas, y torres y aun a la questa y al castillo que es grande espacio de tierra y afirman con mucha verdad la han visto muy a su gusto”.

Ximénez Patón, 1628, fols. 41-42.

“that although so many people come to see it, nobody leaves dissatisfied with the sight of it, because however far away they are, they see it as clearly and distinctly as those who look at it from very close up. Thus it has happened and still happens that because there are so many people there is not enough room for them in the square or around the cathedral, the relic is shown through the windows by the bishop, or in his absence the dean. The people climb up onto roof terraces and towers and even the hill and the castle, which is a long way away, and declare very truthfully that they have seen it to their great satisfaction.”

A greater privilege, however, was to touch it!

Smell and Hearing

... also played a major part. Incense announced the arrival of the Holy Face, along with music and singing in the chapel. Shouts from those who saw it, crowded inside and outside the cathedral, also added to these sounds:

“Los que de diferentes provincias vienen en Romería a ver la Santa Verónica son tantos, que los que la muestran, quanto ven es gente y con tanta devoción que los más lloran y muchos a gritos , porque el señor que a ella tocó y representa, mueve con tanta fuerça por los ojos el coraçón, que a todos admira, espanta y atemoriza y con tanta suavidad enternece que yo testifico que monstrándola me recato muy de ordinario de mirarla – Acuña, 1637, fol. 236v.”

“Those who come on pilgrimages from various provinces to see the Holy Veronica are so numerous that those who show it can see nothing but people, and with such great devotion that most of them are weeping and many are shouting, because the Lord who touched it and whom it depicts moves the heart with such force through the eyes that it amazes, scares and frightens everyone and is so gently moving that I can testify that when it is shown I very often hesitate to look at it.”

More remarkable than sight, smell and hearing was undoubtedly ...

Touch

Pilgrims in the cathedral could touch and kiss the relic as soon as it was taken out of its shrine.

We should not forget what it meant to touch one of the few surviving objects that had been in direct contact with Christ, on which the devotees believed his Face had been imprinted along with his sweat and his blood.

As they circulated inside the cathedral, devotees passed all kinds of objects over the relic’s glass, such as rosaries, pieces of cloth, and above all Veronicas, which, having been ‘touched by the original in Jaén’, as the caption they used to bear indicated, acquired the protective properties of the Jaén relic. Devotees who managed to experience the relic in person were unique among their fellow Christians for having not only the mental recollection of the relic, but the memory of its tactility.

Touching or only seeing: Excesses of devotion

The ‘impulses’ of the cult were driven precisely by the desire to touch the relic.

On the day of the Assumption, the cathedral was much more crowded, solemn and festive and it was then that these excesses occurred, associated with a larger number of the faithful.

We have evidence from the sixteenth century of a desire to limit access of the faithful to the upper galleries of the cathedral, specifically in the time of Cardinal Merino (1527). During the term of Fray Juan Asensio (1690), the faithful were still allowed access, but it was strictly controlled, separating men and women.

José Risueño, Portrait of Bishop Rodrigo Marín y Rubio, c. 1714. Segorbe, Cathedral. Photo: © Catedral de Segorbe.

Bishop Rodrigo Marín and the change of ritual

In 1731, the way the festivity was conducted changed considerably through the initiative of Bishop Rodrigo Marín y Rubio (1714–1732). This prelate ordered a new frame for the Holy Face and a new silver box for its display within the shrine in which it was kept. The piece was made by José Francisco de Valderrama of Córdoba in 1731.

From the moment it was placed in the new frame, the ostension ceremony changed, since contact with the relic was strictly limited. This created great dismay among all the faithful, who could…

The ostension today

The ostension ceremony was discontinued in the 1980s, but not the cult of the Holy Face, which is displayed for veneration every Friday. However, in 2014 the ostension was revived on the traditional dates, Good Friday and the Assumption of the Virgin, and it continues to be shown every Friday in the cathedral shrine.

Research on this important celebration currently continues in order to provide a complete view of it.

Video of the ostension on 15 August 2023. Video: © Catedral de Jaén.

The haptic quality of clothing

Clothing becomes our second skin. All day long, we are exposed to the continuous contact of the textiles that cover our epidermis.

[The] Body and the Cloth are the site and material whereon the beautified edifice of a Person is to be built.

Thomas Carlyle, Sartor Resartus, 1831

Perception of textures

How do we perceive the tactility of what we see, but cannot touch?

Texture affects our perception, causing physical or psychological synesthesia. Viewers who observe an artistic creation through the sense of sight, but cannot touch it, end up connecting what they see with their haptic memory.

We could recognise a texture without seeing it and we could also remember the sensation that it caused us when we wore it, whether we found it pleasant, if we were comfortable or, on the contrary, if it caused us discomfort.

The texture of the second skin

Clothing is made of fabrics and thus fabrics are the essential morphological element constructing our image, mirroring the role we perform in our society. Through the transformative power of fabrics we create our specific identity, which is a unique image that denotes a historical time and a geographical origin. Therefore, clothing can be seen as a ‘second skin’.

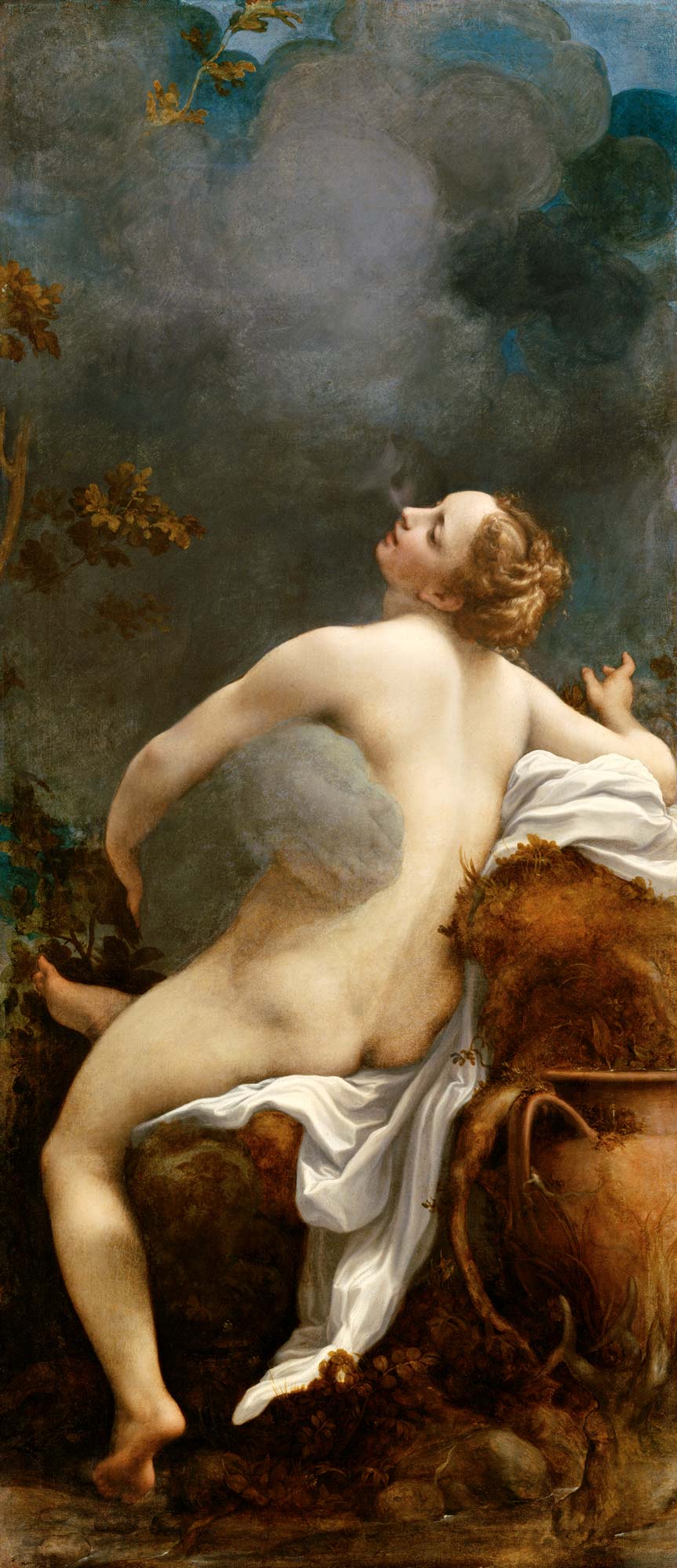

The second skin of the gods: A parade in 1789.

The festivals of the Early Modern Period help us better understand the concept of ‘second skin’.

Richness of textiles and decorations was one of the main characteristics of the costumes in the purest all’antica style worn by the performers of the parade organised by the Ropemakers’ Guild in Málaga in 1789. The fabrics and fibres mentioned in its description arouse many haptic sensations. Let us discover some of them …

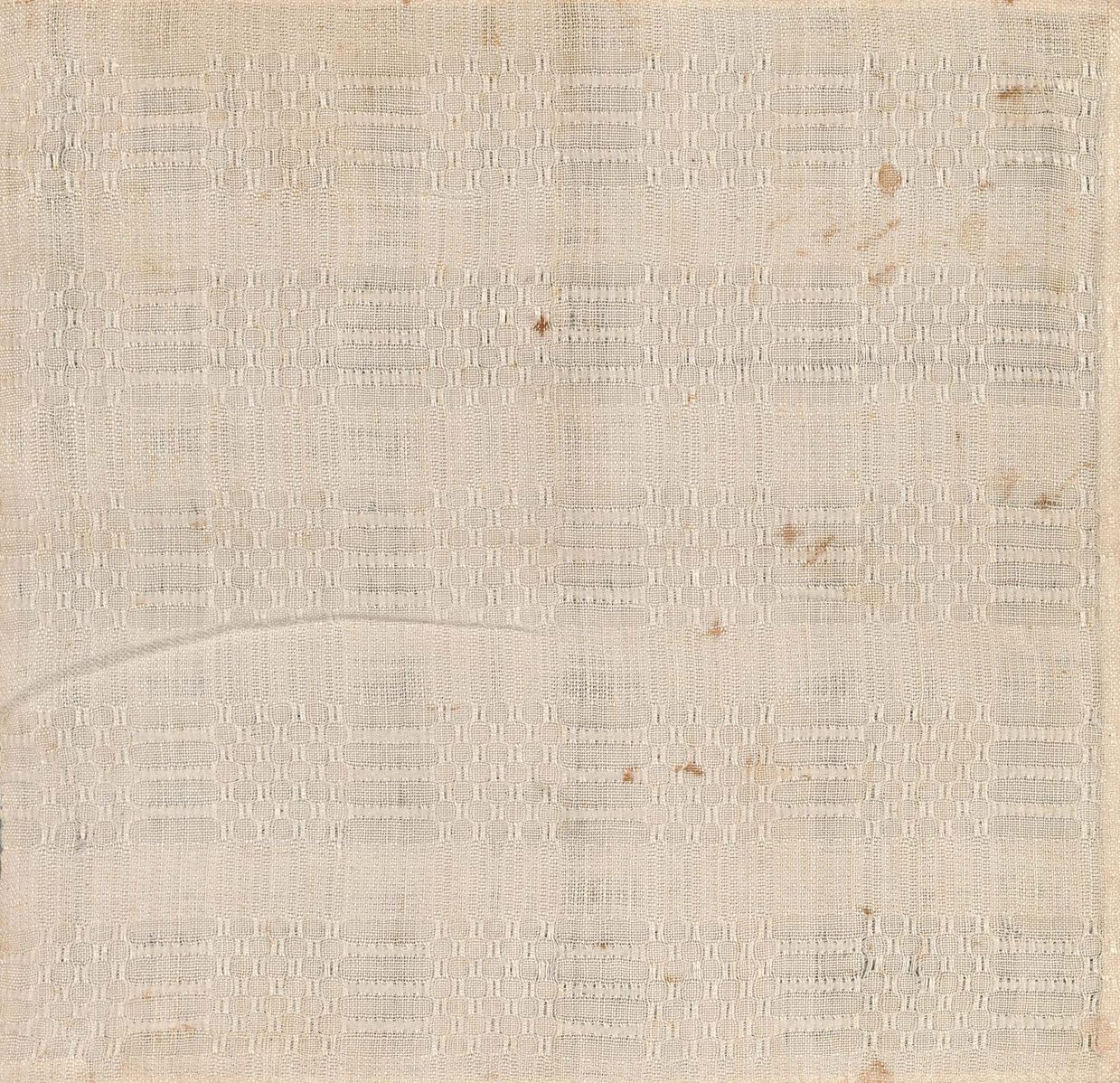

Olandilla

Some gods, such as Pan, Bacchus and Cupid, pretended to be semi-naked by using a very fine linen, that in Spain was called olandilla.

Wool velvet

The god Bacchus wore a cloak of wool velvet (Spanish: tripe) meant to imitate tiger skin (it was possibly painted).

Its texture had to be rough and warm.

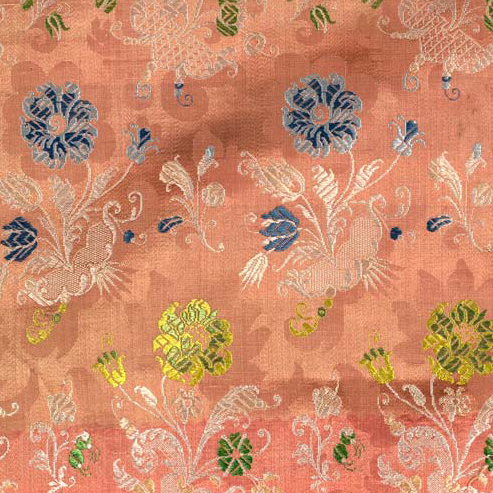

Silk

Silk was the fibre most extensively used in the parade to make garments or small accessories such as cinctures. In the description of the Malaga masquerade of 1789, silk is sometimes mentioned as a component of satins, other times as chamberguillas or silk ribbons. In any case, it was probably woven into many of the fabrics used and not recorded in the text.

Sequins

Many of the gods and goddesses, such as Abundantia, wore fabrics and materials, including the morocco leather of their shoes, which were embroidered with metal sequins and coloured pearls.

Sequins are soft and cold to the touch.

Silver brocade

Silver brocade or silk fabric interwoven with silver or gold were the most frequently used materials.

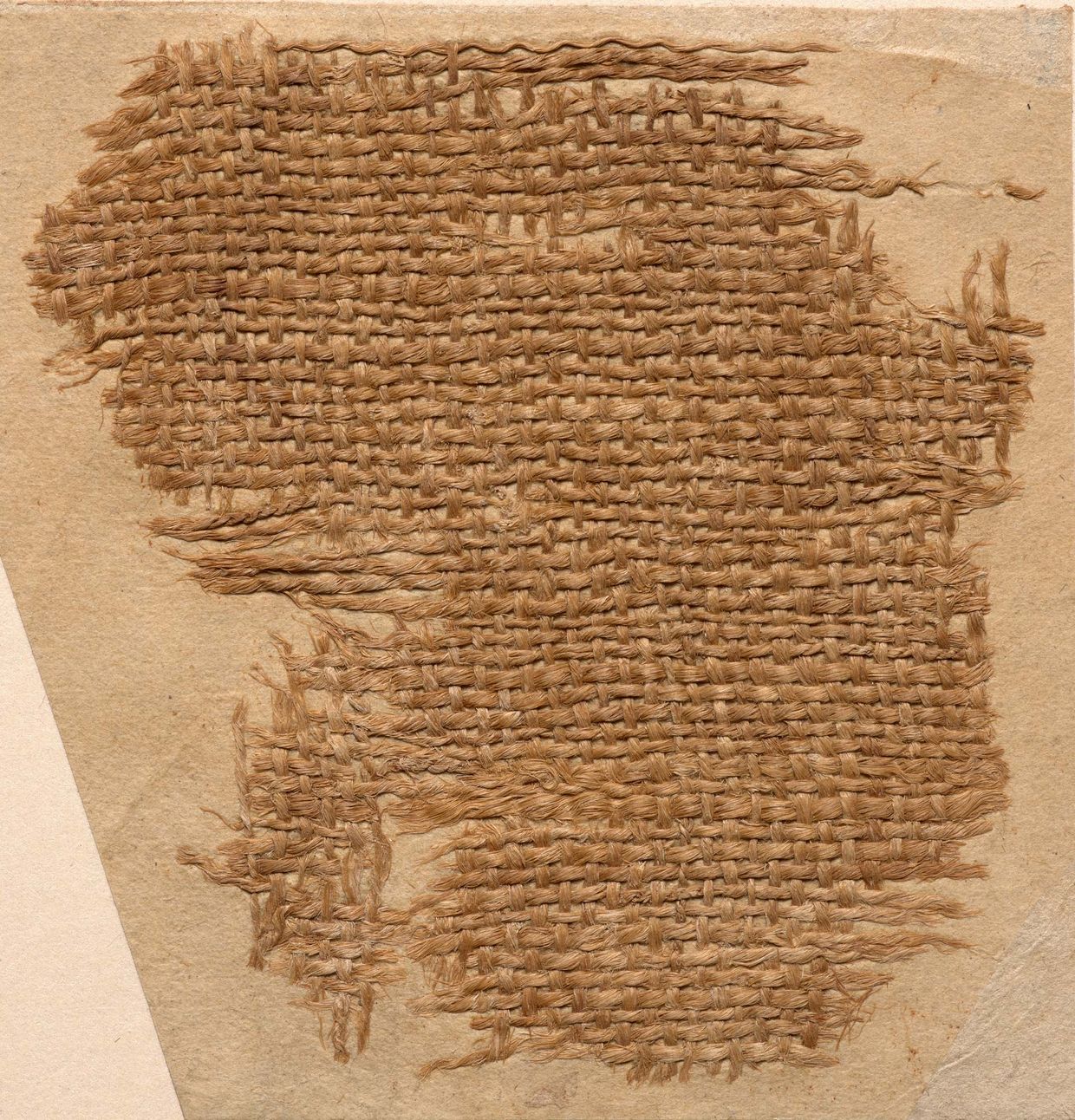

Canvas

Bibliography

Bianconi, Lorenzo e Maria Cristina Casali Predielli. 2018. “Corrado Giaquinto: Carlo Broschi detto il Farinelli”, in I ritratti del Museo della musica di Bologna da padre Martini al Liceo musicale. Firenze: Leo S. Olschki, pp. 103-124.

Carreras, Juan José. 2020. “Farinelli’s Dream: Theatrical Space, Audience and Political Function of Italian Court Opera in 18th-Century Madrid”, in Margaret SCHARRER et al. (eds.), Musiktheater im höfischen Raum des frühneuzeitlichen Europa: Hof – Oper – Architektur. Heidelberg: Heidelberg University Publishing, pp. 357-393.

Castro, Pedro Lopes e. 2018. “Música para a troca das princesas: Estudo comparativo das obras dramáticas comemorativas do duplo enlace entre as monarquias ibéricas (1785)”. Revista Portuguesa de Musicologia, v. 5, nº1 (2018), pp. 39-59.

Correia, Ana Paula Rebelo. 2000. “Fogos de Artifício e Artifícios de Fogo nos séculos XVII e XVIIII: A mais efémera das Artes efémeras”, Arte Efémera em Portugal – catálogo da exposição. João Castel-Branco PEREIRA (Coord.), Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 101-149.

Fernandes, Cristina (coord.). 2018. Dossier temático Música e poder real em Portugal no século XVIII: repertórios, práticas interpretativas e transferências culturais. Revista Portuguesa de Musicologia, vol. 5-1 (1ª parte): http://rpm-ns.pt/index.php/rpm/issue/view/31; vol. 5-2 (2ª parte): http://rpm-ns.pt/index.php/rpm/issue/view/32.

Fernandes, Cristina. 2018. "María Bárbara de Braganza y la cultura musical europea del siglo XVIII, in dossier Música de corte en feminino (coord. Judith Ortega)", Scherzo, Año XXXIII, nº 338 (Marzo 2018), pp. 77-81.

Fernandes, Cristina. 2022. "A Banda Real e outros agrupamentos de instrumentos de sopro e percussão ao serviço da monarquia (1707-1834): perfis profissionais, cerimonial de corte e práticas festivas". In Orquestrar utopias: música, associativismo e transformação social, ed. Maria do Rosário Pestana. Lisboa: Edições Colibri, pp. 115-146.

Flor, Susana et al. 2014. O Palácio Melo e Abreu: História, Património e Laboratório. Contributos para o estudo e salvaguarda do Azulejo de Lisboa, Bispo, Maria Teresa (coord.). Lisboa: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, pp. 95-115.

Flor, Susana Varela. 2016. "Portraits by Feliciano de Almeida (1635-1694) in Cosimo III de' Medici's Gallery", RIHA Journal, 144: 1 – 37.

Flor, Susana Varela; Flor, Pedro. 2018. Retratos do Paço Ducal de Vila Viçosa, vol 6, Col. Livros de muitas Couzas, Monge, Maria de Jesus, (coord.). Caxias-Casa de Massarelos: Fundação da Casa de Bragança.

Flor, Susana Varela e Flor, Pedro. 2018. "Gabriel del Barco y Minusca pintor: elementos para uma visão prosopográfica da Lisboa Barroca". In La Sevilla Lusa, Quiles, Fernando, Fernández Chaves, Manuel e Conde, Antónia Fialho. Sevilla: unibRRC / Univ. Pablo Olavide, pp. 252-287.

Leza, José Máximo (ed.). 2014. Historia de la música en España e Hispanoamérica. La música en el siglo XVIII. Madrid: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Machado, Diogo Barboza. 1747. Biblioteca Lusitana..., Tomo II. Lisboa: na Officina de Ignacio Rodrigues, pp. 765-766.

Mattoso, José (direção), António Manuel Hespanha (coordenador). 1998. História de Portugal. O Antigo Regime (1620-1807), vol. IV. Lisboa: Editorial Estampa.

MECO, José. 2003. A Divina Cintilação: talha, azulejos, mármores, chinoiseries. O Convento dos Cardaes – veios da Memória, Irmã Ana Maria Vieira; Teresa Raposo (Coord.). Lisboa: Edições Quetzal, pp. 116-.

Nery, Rui Vieira. 2008. “Vozes da Cidade: Música no Espaço Público de Lisboa no Final do Antigo Regime.” In Praças Reais: Passado, Presente e Futuro, coord. Miguel Figueira de Faria, 23-44. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte.

Lessa, Elisa, Pedro Moreira e Rodrigo Teodoro de Paula (eds.). 2020. Ouvir e escrever as paisagens sonoras: Abordagens teóricas e (multi)disciplinares. Braga: CEHUM – Universidade do Minho.

Paula, Rodrigo Teodoro de. 2018. “O ‘som brônzeo’ da morte: Poder e liturgia fúnebre a partir da torre sineira da Santa Igreja Patriarcal de Lisboa (1730-69)”. Revista Portuguesa de Musicologia, vol. 5, nº1, pp. 93-116.

Raggi, Giuseppina. 2020. O projeto de D. João V. Lisboa ocidental, Mafra e o urbanismo cenográfico de Filippo Juvarra. Lisboa: Caleidoscópio.

Raggi, Giuseppina, Luís Soares Carneiro (eds.). 2021. Filippo Juvarra, Domenico Scarlatti e il ruolo delle donne nella promozione dell’opera in Portogallo. Roma: Artemide.

Raggi, Giuseppina. 2018. “Trasformare la cultura di corte: La regina Maria Anna d’Asburgo e l’introduzione dell’opera italiana in Portogallo”, RPM. Revista Portuguesa de Musicologia, 5/1: 18-38. Disponível in: https://rpm-ns.pt/index.php/rpm/article/view/339/572 (acesso 10.8.2023).

Sá, Vanda de e Antónia Fialho Conde (eds.). 2019. Paisagens sonoras urbanas: História, Memória e Património [online]. Évora: Publicações do Cidehus. Disponíveis aqui: https://pasev.hcommons.org/outputs/books/

Serrão, Vítor. 2008. O Fresco Maneirista do Paço de Vila Viçosa (1540-1649). Caxias-Casa de Massarelos:Fundação da Casa de Bragança.

Tedim, José Manuel. 2000. “O Triunfo da Festa Barroca. A Troca das Princesas. Arte Efémera em Portugal – catálogo da exposição, João Castel-Branco PEREIRA (coord.), Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, pp. 174-215.

Tércio, Daniel. 1999. Dança e Azulejaria no Teatro do Mundo. Lisboa: Inapa.

Credits

| Title | Between Heaven and Earth |

| Coordination | Isabel Alba Nieva |

| Authors | Isabel Alba Nieva, Felipe Serrano |

| English proofreading and voice | Alexander McCargar |